These poems and the essay following will appear in the anthology On the Endless Horizon: A Poet’s Field Guide to Literary Translation, forthcoming from W.W. Norton in 2014.

Choćbyście unicestwili

|

Even if You Annihilated

|

|

Jak pisać?

Głodnego trzeba nakarmić |

How to Write?

One has to feed the hungry |

|

***

Inne

|

***

Other Ones

|

|

| ***

W tym roku tylko liście boję się, Rabbi, boję się, Panie, że mnie przeklnie głodny strudzony |

***

This year only leaves I am afraid, Rabbi, I am afraid, Lord, to be cursed by the hungry man weary of |

|

Drzwi

w akcie oskarżenia |

The Door

in the indictment |

Reality hurts us into poetry

For a long time Polish poetry has embraced the Romantic heritage. It has been inseparably linked to the Polish nation. One of the reasons was that since 1795, when Poland (under the name of Nobles’ Commonwealth) ceased to exist, Polish culture became a substitute for Polish institutions. Finally, in 1918, poets attempted to cast off the cloak of militant poetry, that is to say, poetry speaking on behalf of the nation. One of them was a poet Jan Lechoń who belonged to Skamander Group. His line: “And in the spring let me see spring, not Poland” became a manifesto. Yet during the period of Stalinism and Communism this Romantic understanding of the poet as a missionary and national bard reasserted itself.

A poet had a special calling. Czesław Miłosz says: “What is poetry that does not save nations?” In the next literary generation, in his poem “Stronger than fear,” Ryszard Krynicki asks: “What is poetry if not the voice of conscience,” the one that neither regime nor cleansing can annihilate (Krynicki 217)? In another poem he says:

all our testimonies,

still mute tree rings,

still our mute bones will tell

what times we lived in.

(Krynicki 206)

Ryszard Krynicki belonged to the New Wave Generation, poets who made their debut after 1968 (Stanisław Barańczak, Adam Zagajewski, and Ewa Lipska, just to mention the most representative). The poets of New Wave believed in poetry as a witness to truth and as a responsibility. In a poem “How to Write?” Krynicki poses a question: “To write so the hungry man / thinks it’s bread?” And then he continues in the same poem: “One has to feed the hungry / and write so the hunger / does not go to waste” (264). Krynicki believed that poetry constituted the conscience of society. Together with Zagajewski and Barańczak he contested the “newspeak” widespread by mainstream media under the Communist Party. His distrust in reality led to “the conscience, which is constantly endangered by outer constraints and the possibility of inner stultification, alert and thereby hopes to heal the disturbed, sickened sense of self-esteem” (Karl Dedecius). The New Wave generation insisted on the necessity of addressing politics in their writing and debunking the ideological lies. In his poem “Truth” from the collection Komunikat (“Announcement”), Zagajewski writes: “Say the truth, that’s why you serve.” Hence, in poetry of The New Wave there is no place for relativism. Instead, the New Wave poets propose a new realism which links ethics and aesthetics.

Krynicki’s verses remind us that poetry is a tribute to Mystery and Silence.

I do not know if I have the right

to speak, to be silent, to touch

the wounds. I pray. Without

words. He

Knows.

(232)

In another poem, he writes:

Poems? Voices?

Lupine and doe-complaints

Through me runs the stream

of beauty? Of despair and regret

For that I am silent.

(282)

Krynicki’s silence in poetry comes from the desire to reduce all the noises and distractions in order to reach under the skin of the world. He rejects the fireworks of speech, rather choosing austerity with no adornments. It comes from both attention and obedience to silence, just as the Latin word audire signifies both: to listen and to obey. Poetry in Krynicki’s cosmogony comes from the purity of heart: ascetism. It wants to reach under the bark of trees via lucid moments found in concrete and small, if not insignificant, objects/animals (such as a little snail met on a road). Such writing points to a new type of realism saturated in epiphanies of ordinary things. By elevating ordinary moments to the level of the Sacred, Krynicki validates every small and minute detail of existence. In order to “de-create,” in order to reach under the alphabet to get to its primeval form, to the Glagolithic alphabet, one has to practice ascetism; one has to be pure of heart and silent. One needs “to touch the heart of the matter…inside the stone,” as he writes in yet another poem, “To Touch”:

“To touch the heart of the matter.”

I have dreamt once

I was touching the heart of the matter.

Groping my way, from the center,

inside the stone.

(366)

The above poem brings us back to the issues of translation. How to get to the heart of the matter in translating Krynicki’s poems into English? How to translate the soul of the poem, or, in philosopher Susan Langer and cognitivist Margaret Freeman’s term, “the semblance of felt life” (292; 717-752)? When Emily Dickinson sent her poems to Higginson – the editor of Atlantic Monthly – she asked whether her verse was alive. When I translate Krynicki into English, I ask the same question: “Is his verse alive in English?” After all, as Goethe used to say, “whoever wants to understand the poet must go to the poet’s land.” To experience the profoundness of Krynicki’s poems, one has to understand the context he wrote in, the Stalinist regime and the mentality of Polish people. How to get from here and now to Poland as it was then?

In theology, translation implies the act of miraculous displacement just like in Nicolas Poussin’s 1630s painting: “The Translation of St Rita of Cascia.” St. Rita was miraculously transported into a place where she desired to be. Translation is a way of being in two places at once. This miraculous transport, this bilocation, is a theological meaning of translation.

The original poem in translation is a little like a dybbuk that enters the foreign language in order to fulfill its destiny. In Musical Variations on Jewish Thought, Olivier Revault D’Allonnes writes:

The translator is only a midwife who recognizes the insufficiency of the source and target language entrusted to her/him. After all, the translation is the testimony to both the human desire and inability to express the ineffable. Yet, by translating we are prolonging the life of the poem, we are multiplying it. We practice bilocation in love.

_____________________________________

Works Cited:

Freeman, Margaret. “The Aesthetics of Human Experience: Minding, Metaphor, and Icon in Poetic Expression.” Poetics Today 32.4, 2011.

Krynicki, Ryszard. Wiersze Wybrane. Kraków, Poland: a5, 2009.

Langer, S. K. Feeling and Form. New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1953.

Revault D’Allonnes, Olivier. Musical Variations on Jewish Thought. New York: Braziller, 1984.

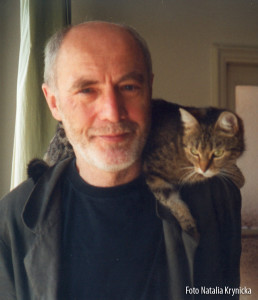

Ryszard Krynicki was born in 1943 in Sankt Valentin, Austria. He is representative of the ‘new wave’ group of poets, formed in the late ’60s to oppose the Soviet regime. Due to his anti-government political activities, Krynicki was banned from publication for several years. He has published many books of poems, the most recent being Wiersze Wybrane [Selected Poems] in 2009 and Przekreślony Początek [Crossed-out Beginning] in 2013. Krynicki has also translated many German authors, such as Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan, Bertolt Brecht, and Reiner Kunze. He has received many prizes, most recently the Friedrich Gundolf Prize in 2000. Krynicki lives in Krakow where, together with his wife, he runs the publishing house a5.

Ryszard Krynicki was born in 1943 in Sankt Valentin, Austria. He is representative of the ‘new wave’ group of poets, formed in the late ’60s to oppose the Soviet regime. Due to his anti-government political activities, Krynicki was banned from publication for several years. He has published many books of poems, the most recent being Wiersze Wybrane [Selected Poems] in 2009 and Przekreślony Początek [Crossed-out Beginning] in 2013. Krynicki has also translated many German authors, such as Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan, Bertolt Brecht, and Reiner Kunze. He has received many prizes, most recently the Friedrich Gundolf Prize in 2000. Krynicki lives in Krakow where, together with his wife, he runs the publishing house a5. Ewa Chrusciel has two books in Polish: Furkot and Sopilki, and one book in English, Strata, which won the 2009 international book contest and was published with Emergency Press in 2011. Her second book in English, Contraband of Hoopoe, is forthcoming with Omnidawn Press in September 2014. Her poems were featured in Jubilat, Boston Review, Colorado Review, Lana Turner, Spoon River Review, and Aufgabe, among others. She translated Jack London, Joseph Conrad, I.B. Singer, Jorie Graham, Lyn Hejinian, and Cole Swensen into Polish. She teaches at Colby-Sawyer College.

Ewa Chrusciel has two books in Polish: Furkot and Sopilki, and one book in English, Strata, which won the 2009 international book contest and was published with Emergency Press in 2011. Her second book in English, Contraband of Hoopoe, is forthcoming with Omnidawn Press in September 2014. Her poems were featured in Jubilat, Boston Review, Colorado Review, Lana Turner, Spoon River Review, and Aufgabe, among others. She translated Jack London, Joseph Conrad, I.B. Singer, Jorie Graham, Lyn Hejinian, and Cole Swensen into Polish. She teaches at Colby-Sawyer College.

Photo: Michael Seamans