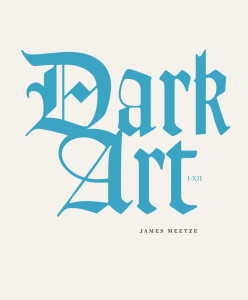

Dark Art, I-XII

Dark Art, I-XII

James Meetze

Manor House Monographs, 2013

ISBN: 9780985909536

Charles Frazer in his treatise on magic, The Golden Bough, asserts that:

Meetze, in the twelve poems included in Dark Art, is aware of this Law of Contact—inscribed into the back cover are three light-blue lines from poem VII:

how light happens; every filament

burns toward its end like we do.

With this, Meetze adopts the role of an alchemist, assuring us of his knowledge of the very first causes, the separation of light and dark. Then, using Frazer’s Law of Similarity, he connects us to this old magic, telling us that we, as well, are part of this process. Throughout these poems, our participation is assumed; for example from Dark Art’s opening poem, “Council”:

more than I do

when our heads flood

with all the voices […]

When America over-

flows within us.

No one wants

to be a river

more than we

Throughout, Meetze addresses the reader and connects us, aware that meaning is created through interaction, almost creating spells of sorts with each poem. In “Dark Art IV” this creation becomes more explicit:

They are magicked into being

in our throats, our mouths, in air, to say

“where language fails, poetry begins.”[1]

So as we read these poems, attention to their genesis is paid, creating a sort of cognitive reverb. As these poems are birthed (in mouths and throats), so too they dissipate into air almost simultaneously. And perhaps this too-fast dissipation is what leads to a desire for more materiality, a desire to “hocus pocus you into my arms” (“Dark Art VIII”). This direct address might assume much about the “you” reading it, but because the poems seek to connect, as the title directs, the personal experience of language to the numen of everything else (“We have begun to say how nimble words can be: […] Feel how they tumble in your fingers / pieces of dust, pieces of stone, pieces of the story” (“Dark Art IX”)), this intimacy is necessary, keeping the poems from drifting apart or into a didactic cosmology. Then again, perhaps as Meetze writes in “Dark Art VII,” “The order of the poem is arbitrary, / like constellations are; the recipient / of it draws a line from here to here.”

Like Wallace Stevens before him, these poems share a concern with the relation between the real and the imagined. Meaning which is inherent and which is created. Roy Harvey Pearce, writing about Stevens, says of this concern, “What we have is the imagining self and a reality which is not part of that self, but which for the sake of belief must somehow be made a part of it” (“Wallace Stevens: The life of imagination,” 1963). As a lens, this offers one way of looking at Dark Art—Meetze’s lines like “Narrative arcs will always intersect / our real lives in a circle” and “There is a translation of birdsong for orchestra” presents us with Meetze’s insistent, and lyric, exploration of this connection between the abstract and the real.

Yet unlike Stevens, I am uncertain that Meetze believes “that for the sake of belief” we must be made a part of it. Rather, these poems make the assumption of connectivity, but explore, and thus question, the nature of that connection. Unlike the arch-rationalist Stevens, Meetze employs magical thinking to create correspondences, finding or perhaps defining what magic is as he goes with lines like, “Look how magical it is to gaze at a glowing / screen and interact with our evolving storyline” (“Dark Art X”). And with this thinking seeks to place us in time and context.

the fuzzy inaccurate revisions, the magic

in idle life we reconnoiter to be better engineers

of our own uncertain destiny

[…]

We are here. I am among us with a song

that is every sound the world makes without words.

Silence is the place of true language

speaking with what breath all of us have.

I sit her and say there, my tired heart

there are those words we know

and use only as incantations.

(“Dark Art XII”).

Reading these poems (the first time, flying back across the state several thousand feet in the air during some very rough weather), I found myself thinking of the archetypal shaman / magician / hermit which roamed through them. Perhaps with the fear of possible annihilation, this particular reader was more open to ideas of magic, but later, once more on terra firma, I was reminded of David Abram’s assertion in Becoming Animal, “to step into the shadow of this mountain is to step directly into the mountain’s influence, letting it untangle your senses as the rhythm of your breath adjusts to its breathing, to the style of weather. To step into its shadow is to become a part, if only for this moment, of the mountain’s life” (21). Stepping into Dark Art is to allow yourself to move into its sphere of influence, to acknowledge the Law of Connection that now exists between you and the text, which is as Meetze asserts, “the darkest of arts.”

Dark Art, I-XII is hand-sewn in an edition of 150 with a letter-pressed cover courtesy of Daniel Heffernan at Clove St. Press. It includes a frontispiece by Debra Scacco, which evoked in the viewer ideas of geography, time, and fragments. The chapbook is well-designed and at 22 pages and just under 6.5 x 7.5, gives enough space to the poems and fits nicely in the hand.

1. A line from Andrew Joron’s The Cry at Zero. back

Works Cited

Abram, David. Becoming Animal, and earthly cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books, 2010. Print.

Frazer, Sir James George. The Golden Bough, a study in magic and religion. Abridged edition. London: MacMillan and Co., Limited, 1929. Print.

Pearce, Roy Harvey. Wallace Stevens, a collection of critical essays. Ed. Marie Borroff. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1963. Print.

Trevor Calvert is a librarian living in the East Bay who writes reviews and poetry, and co-edits Spooky Actions Books. He is the author of Rarer & More Wonderful (Scrambler Books), and North gives flesh to wind (Little Red Leaves Textile series). His work has been included in Bay Poetics (Faux Press) and Involuntary Vision: After Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (Avenue B Press) as well as online at the Volta, BlazeVOX, NOO Journal, and others.

Trevor Calvert is a librarian living in the East Bay who writes reviews and poetry, and co-edits Spooky Actions Books. He is the author of Rarer & More Wonderful (Scrambler Books), and North gives flesh to wind (Little Red Leaves Textile series). His work has been included in Bay Poetics (Faux Press) and Involuntary Vision: After Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (Avenue B Press) as well as online at the Volta, BlazeVOX, NOO Journal, and others.