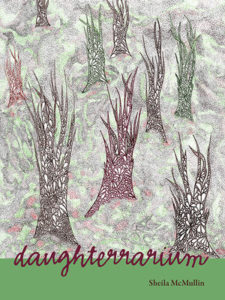

Sheila McMullin

daughterrarium

Cleveland State University Poetry Center, April 2017

In his essay “On Restlessness,” Carl Phillips writes “whether confessional or not, every poem is in part a record of an engagement between our conscious and unconscious selves—it is why poetry can be so dangerous.” Sheila McMullin’s daughterrarium, winner of the 2016 Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Competition, is a record of such engagement. And, yes, the book, concerned with breaking silence, feels dangerous, exhilaratingly so: “I work toward an anger that moves forward//Maybe it is quiet but it’s not silent/Maybe it is getting louder.” (p. 77)

McMullin sculpts this taut work from dream-logic and memory, visceral experience, what the body—the female body—holds. She uncovers histories, violence-against, exploitation, and the fear, shame, anger, and silences that live within the various speakers. Given our current socio-political landscape, the book is timely and necessary.

The first poem, “Tapering,” begins with a curiously placed asterisk: “The day woke with a (*) / not a star, but a satellite.” (p. 1) The day itself wakes in motion, like a satellite. The speaker and her mother are driving through New Mexico, leaving home, running away:

while driving:

When I was in my twenties

I thought if there was a gun around

I might have held it toward myself (p. 1)

Perhaps because the space is already fraught with leaving, the mother feels compelled to disclose her suicidal thinking to her daughter. Note the curious (I). Is this I in isolation? Or contained by certain parameters, some of which are spatial and familial—and in this moment of the poem, the I in a car, her mother revealing a hard truth, she literally cannot get away. Suicidal depression is often genetic. The poem ends with the speaker’s own admission: “like killing myself had never come/into my own before, no/My tongue dried with half the pill.” (p. 2)

Throughout the collection, McMullin harnesses the power of recurrence. In “Tapering,” as we saw, mother and daughter have lived with depression. Elsewhere, words and lines repeat and/or are recombined, becoming leitmotifs allowing us to trace patterns, to feel through language and image how it feels to be one woman coming into consciousness of the similarities among women while maintaining a sense of the individual voice, the (I).

The poems “Ruth’s Book,” “Olga’s Book,” “Judith’s Book,” “Clara’s Book,” and “Lilith’s Book” enact the experiences of five women, each in her way mis-recognized, dismissed, categorized. Here, repetition serves to haunt, disturb, and, in some ways, free. A vatic voice, perhaps a nun, Clara speaks of being entered by God, bringing about a confusion of selves-and-situation: “easier to see how (when) he (it) does/not protect you, mimosa/burn when I (you) squat, burning sage/loosen when you (I) bleed, roasting rosemary.” (p. 90) Participant and observer, Clara both feels and watches her body burn. The burning is infection and remedy, hurt and the scent which cures. Rosemary, infection and burning recur in “Lilith’s Book:”

over a febrile body.

A constellation.

Let it burn.

Mirrors and poppies.

The should-be-shamed

naked woman

vesper, rebuilding her own house.

My body, blue rosemary cloak, blooming ocean. (pp. 91-2)

Lilith imagines, or dreams, being on the street, middle of the night, a fire burning —maybe her house, maybe inside her. Objectified, judged, she’s seen but not really seen. “Let it burn,” she says, claiming the heat. Rosemary covers her, perhaps literally and also for remembrance, the self-remembering possible in lyric space. That different voices speak the same words creates an echo chamber, a sense of repetition and lineage, what passes house to house, generation to generation, through women’s lives.

Also traced through this work is the speaker-self’s alienation from her feeling, perceiving body. Several poems bear the titles “Bad Woman” plus variation: “Bad woman: reverse ghost variation,” “Bad Woman: broken ballad variation,” etc. In “Bad Woman: thought drawer variation,” the speaker recounts an exploitive sexual encounter: “A boy sticks his dick in her ass and then in her vagina./A few days later her skin burns/and rises to 105 degrees.” (p. 3) Again, there’s burning, infection, fever. The poem examines the fallout from this experience. A doctor is patronizing; her mother insists she protect herself by keeping silent. As well, a child climbs a tree, licking sap from her fingers, experiencing intimacy with the tree; a woman is robbed at gunpoint; another sees ghosts. These trajectories seem connected only tangentially. As the poem draws to a close, we see that each of these selves is the speaker:

did as she was told,

said sorry for the things I did wrong.

I practiced cleanliness and safety first.

When they came, I was unprepared

and they took me away from myself. (p. 9)

Most women in this culture can, I imagine, relate to these stunning lines, for we are, in myriad ways, taken away from ourselves. Other “Bad Women” poems explore, through dream, imagination, and image, fragmentation, perception, and the process of reclamation.

Pages of italicized, right-justified, untitled poems separate groupings of titled poems. These serve as linkages that identify emotional realities and break the silence. Fear, anger, guilt, shame and hurt are named finally—for the greatest wound and danger to women is silencing: “The life being built around me/looks nothing like the heart inside my heart //Guilt coerces me into silence.” (p. 71) A few pages later, “Trust me with my body,” the speaker asserts. “Gods are in my movements//You don’t have to support me/You have to get out of my way.” (p. 75, 77)

Words have power both to name experience and to imagine how it might be different. The book ends on a lyric beat: “I put the ginger flower in my mouth./Orchards bloom inside me.” (p. 98) Tasting the flower in lieu of “half the pill,” claiming as ally the potency of words, daughterrarium insists on being dangerous to the structures that keep women from speaking our truths.