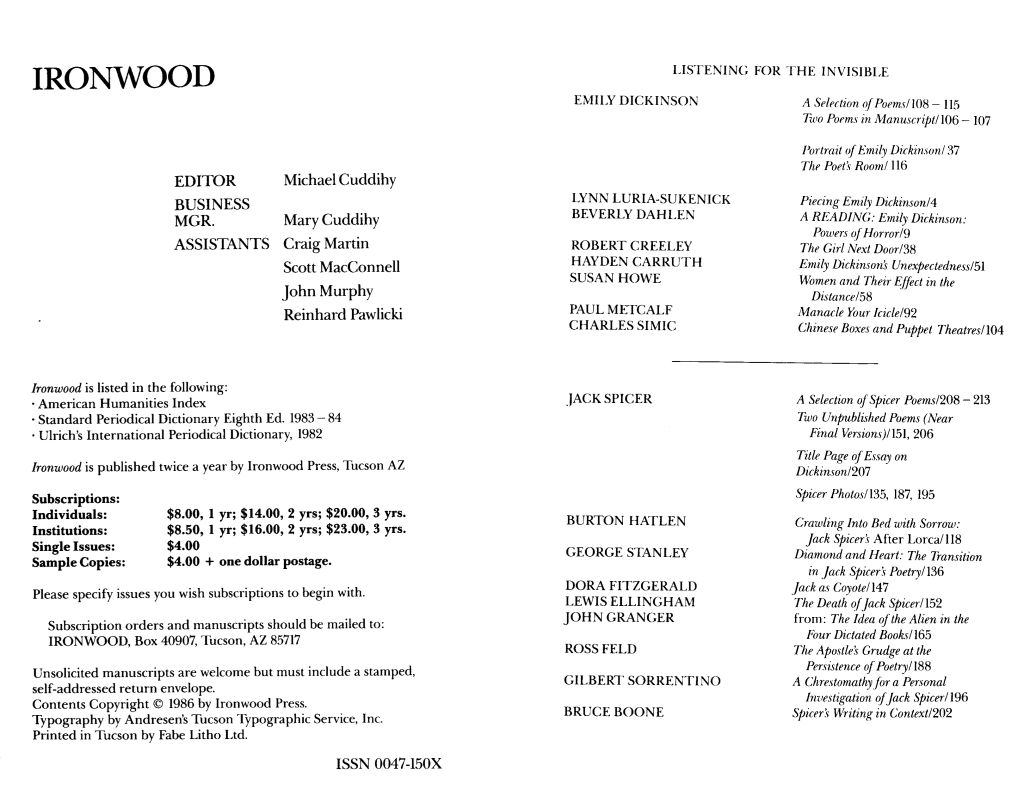

What follows is a transcription of the first 53 minutes of a trio of informal talks on Emily Dickinson given by Robert Creeley at New College, San Francisco in the fall of 1985 and recorded by David Levi Strauss. The transcript originally appeared in a 1986 issue of Michael Cuddihy’s terrific magazine Ironwood—issue number 28, entitled “Listening for the Invisible”—that was devoted to the work of both Dickinson and Jack Spicer. Complete recordings of these talks are available online at Creeley’s PennSound page.

I know of no formal essay on Dickinson by Creeley, but she remained an important figure for him throughout his life, from the high-school anecdote he relates at the beginning of this transcript to the terrific late essay “Reflections on Whitman in Age,” in which he cites “There’s a certain Slant of light” as a poem akin to Whitman’s “Old Age’s Lambent Peaks” in that both make evident “writing with a habit so deep and familiar it no longer separates from [the writer] as an art or intention.”

During my time in Buffalo, Bob and I talked of Dickinson many times, though he never mentioned to me that he’d given these talks. I stumbled across the Ironwood issue shortly after he died, and I only recently noticed that the recordings had been added to the PennSound site. It’s my hope that reprinting the first near-hour of Creeley’s engagement with Dickinson will encourage readers to listen to his talks in their entirety.

The Ironwood issue says this talk occurred on October 20, 1985; the PennSound site says September 20 of the same year. Though I’ve relied heavily on the Ironwood transcript, I’ve made numerous changes for the sake of accuracy and clarity. Many thanks to Gillian Hamel for her help with this task.

THE GIRL NEXT DOOR

As a kid growing up in New England, in West Acton particularly, literally, this poet was primary and close. Her ways of feeling the world were extraordinary but also remarkably familiar. And I think the first time I can remember specifically was the time when we were asked in the high school class to memorize some poem. I must have been using a general anthology. I remember I chose a poem of hers that has the classic line “Inebriate of air am I” and because I wasn’t that sure as yet I remember I got the poem correctly except for that line which I had translated to read, “I am an inebriate of air.” And in some peculiar way it begins then: not only the engagement with ways she was feeling and thinking the world or that the fact of her feeling was such an information of her thinking and vice versa so that there was virtually no separation, but that kinds of subtlety of hearing began to be insistent and began to be specific from my habits as well as those so obviously hers. I never felt in a funny way that I even recognized her as eccentric growing up in a—well, having for instance—a family, my uncle’s family, living just next door to us and having them not speak to me for five years. They came and went, they didn’t stay in the house but they certainly were uncommunicative. And then also in this even smaller town, the incidence of eccentric behavior was so persistent that it was literally unremarkable. So that I am not trying to mitigate or to generalize her particular life, but I am trying to say that it’s peculiar, the isolation of details within it and the peculiar inflation of these too, to try to prove an explanation: a failed love or a defeated, you know a defeated sense of what’s out there, etc., etc. All of that way of reading her seems to me both offensive and tacitly condescending.

In trying to get myself equipped to talk in this manner for three evenings, I began actually by going to the library and getting very simple and obvious texts relating. I began last spring by reading, usually late at night, reading Richard Sewall’s biography which I found very useful and very attractive, if you want a primary information of her. I have in one sense no, you know, scholarly measure but it seems to me a very detailed and articulate rehearsal of the known facts of her life and relationships. And then I also read at that time a more recent biographical information of her brother Austin and Mabel Todd’s relationship which was fascinating for many reasons. First of all, it tended to qualify the sense of this utterly isolated person; I mean the Emily Dickinson that was proposed to me as a person, let’s say in college, was this neurasthenic, utterly withdrawn, as though no whiff or factor of usual common existence ever got to her. She lived in this immaculate enclosure of tortured sensibility. I didn’t read the poems as saying that, but that was the information one had of her. So I found this very much a relief to realize that Austin and Mabel used in fact that very house for their assignations and that Emily Dickinson was certainly alert enough to recognize the activity. And then I was charmed for instance that her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson becomes—well, she’s very irritated at this point with I think not only with Emily Dickinson but with much of Amherst as well. (She’s been a kind of grande dame of the society.) And again if one wants to, one can certainly manufacture a number of psychological bases for her disposition: she comes of a vulnerable family; her father is very questionable so it’s been an advantageous match for her, certainly, to marry Austin, to marry into the Dickinson pattern which is one of very solid state at that point in Amherst. Her father has some problems—no it’s her grandfather, Samuel. But in any case the family’s situation is now very solid and he has both political recognition, yeah he’s a decisive politician of the state, a lawyer; he’s also, as had been his father before him, the treasurer of Amherst College, etc., etc. So the Dickinsons are a very substantial family in the place and time. In any case, Sue Dickinson talking to the newly arrived Mabel Todd who suggests she would love to introduce her husband to the sisters Emily and Lavinia, and Susan’s remark is, well, she would highly question that impulse, simply that the last time she was in the house, she discovered her sister-in-law in the arms of a man in the parlour. That’s very interesting. It must have been when Emily Dickinson was at least in her forties, so she was not entirely reclusive at that point. Nor does she prove so anyhow. I’m not again trying to simply generalize but I want to get rid of some sense of person who is reactive, faded, fragile. I think she’s an extraordinary survivor. I was saying to Robert Duncan earlier, just a few minutes ago, I felt this, reading both her poems and also of the facts of her life, there was a peculiar echo of, paradoxically, Charles Olson, who wouldn’t strike one as an immediate parallel. But the will of those two people is very similar. I kept thinking Olson’s “I have sacrificed everything, you know, to have this concentration or to enact this vision or this being I imagine as the poet.” And like Emily Dickinson, Olson also is careful to try at least, however legitimately, to differentiate himself from the me or the I factor of the Maximus Poems just as she, you recall in a letter to Higginson, makes the point that the me is not her. That’s very subtle and obviously a point that one could qualify. I think each was using an imagination of themselves in some intensive and extensive manner.

Again, in conversation with Robert just a few minutes ago, we were thinking as with Whitman, the determined creation of a persona, the very deliberate style of dress, in her case the insistent white that she wears in later years, Whitman’s slouch hat, open shirt, all of the very determined creation of a figure, etc., etc., etc. As one reads the various informations of her as a child, as a kid, again there is Sewall’s biography. Another extraordinary resource for me is Jay Leyda’s The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. It’s a fascinating book. It’s an attempt to make a complex grid or context or collage of diverse public and personal informations of the literal days and situations of daily living so that one gets not simply the intensive focus upon the singularity of this person but a sense of the complex interactions and public events and social dispositions and habits that were the common information. Something for example that would be—you know I wish and I wanted to come with some very simple slides, let’s say, that would give you a physical sense of her, where she lived, even though it’s been, it’s changed significantly in the hundred years and more since, but simply the disposition of the houses, what the town’s grid was like, what would one presume to be the usual comings and goings, not only from the house but on the street. The church for example, the Congregationalist church that’s so significant for the family is literally within a very short walk further down the street and it is the mainstay of the then fading Puritan authority of the town. I found for instance that Amherst was begun as a college to act as a rectification of the backsliding into a more generalized, almost Unitarian disposition that Harvard was felt to have fallen into. That is, Amherst was to regain the strong Calvinist base that Harvard had begun with but had now seemingly lost. This is the college that effectually her grandfather more or less beggars himself to help secure. And the homestead is the house that she eventually comes to live in when her father manages to buy it back into the family’s possession. It’s there that she effectually lives most significantly and sadly dies.

The person that one meets initially is a kind of lovely, fey, and attractive kid with a vivid, articulate, and social imagination. Again, if one thinks of contemporary circumstance and even of towns one might presume to have old time familial habits, I don’t think one could very simply gain a sense of the density or the daily interactions that must have been common at that time. I would have had some slight echoes of it, I would have had truly echoes of it in my grandmother’s conversation and habits: the authority of communal or public events whether church or secular, the common chatting, the endless cups of tea or the endless droppings in, comings and goings. For instance, the fact of her sending as almost notes of affection and thanks the endless notes and bits of pastry or cake, swapping of recipes, flowers, lovely quick alert wry poems that are endlessly sort of issuing from her house, her room literally, to neighbors and friends of her affection aren’t singular only to her. They come back, by which I mean that there are equally very similar responses of equal little cakes, flowers, notes, endlessly passing so that one can’t again think of her as someone who’s acting simply in an utterly isolated and eccentric manner. Her use of it is singular and the genius that informs these extraordinary notes is certainly singular to her as a writer but the occasion is very familiar. Also, the characteristic rhetoric certainly has a firm base not only in the religious oratory of the period but also in the common sense of a communal and communally shared and heightened rhetoric that can pass into a very mawkish and bland echo but nonetheless has the habit of that need to express oneself distinctly, and if not melodramatically, at least in a way that gives a vividness to that which is being said. So that too, another thing that comes quickly to hand as one reads her life would qualify the imagination of her being primarily self-taught. I can’t imagine a writer who isn’t. By which I mean only this, that the sense of her being an ill-educated person or someone who has had only a meager resource of that kind gets quickly dispelled if you read the background of her education.

She has one of the most sort of distinct secondary-school that I think you could possibly have at the time. Amherst Academy, to which she goes as a kid, has a very sophisticated educational base and would probably beggar any equivalent grammar school of the contemporary period in terms of what it had to teach and the resources it had in that teaching. It got for instance, characteristically it got a lot of the young coming variously from Amherst as graduates and/or those from schools equivalent. So it had a very bright enclave of somewhat transient but certainly persistent bright people, and usually bright people at an initial point of their professional commitments to teaching. And the headmaster at the school, Mr. Humphrey at the time I think his name was, was exceptionally vivid in this way. He gives her for example—not he gives her personally—he doesn’t write it down on a paper and say here Miss Dickinson, use these words or these associations, but it seemingly turns out that a lot of her so-called scientific vocabulary or the basis for that wildly alert juxtaposition of scientific data with other terms of emotional and/or human preoccupation is largely based on the education she was getting when she was 13, 14, 15. Too, if one reads her letters of that time, letters she’s writing characteristically at the ages of 14 or 15 either to her brother or to her friends, their intelligence and articulation is certainly a trained one.

This is not a simply natural intelligence expressing itself in a commonly accessible language. She’s a privileged kid. I always felt it a kind of confusion, mine most of all—I had for years the imagination of Williams as, if not a son of the working classes, at least someone whose basic information had been got harshly, from the streets. Forget it. I mean he came from a very very solid middle-class base with an exceptional education thus given him. Just so Emily Dickinson. Too, the fact of her father’s activity and authority, the persons who were commonly in and out of the house were equivalent in their abilities and authorities. If one thinks of the people who come closest to her emotions and affections, they are without exception persons with remarkable public authority. The last determined love of her life, Judge Otis Lord, is a Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice, an extraordinary articulate and powerful person within the legal and intellectual base of the state. That’s a fascinating relationship. One wishes that his letters had survived. They don’t. I think there’s one, one to her sister Lavinia. Reading it, one recognizes as both Leyda and Sewall emphasize: this is no charity; this is an extraordinarily committed care for this person, not simply as a friend but as someone who obviously and distinctly loves her. So that what I’m trying only to do with this sketching or with this quick kind of almost glib reference is to gain some recognition of the initial place, possibly, but also the initial person. She has an older brother Austin, born, what, about a year previous to her. (The children come in quick succession. Her mother I think at the time she’s born (1830) is about 25.) Her brother’s been born I think about a year before (Austin), maybe a year and a half, then her sister Lavinia.

The father again has been given a peculiar judgment. And I think too, if one’s reading backwards into the terms of the how-it-is-that-she’s-this-writer, one wants to presume this harsh and stern and dictatorial person. At least reading the data in either of these two books, he’s far more—you can’t call him exactly playful—I don’t think any father of that period could be probably unless… And it isn’t simply her affection for him which is very marked—I mean she has the lovely sort of charitable, accommodating, slightly pitying instincts of the classic daughter, at least of this period and those subsequent. She knows her father very well and she knows his vulnerabilities. She describes, for example, going to a concert of, I think, Nellie Melba and her father’s both awed and aghast by what he’s hearing. He can’t quite believe that this extraordinary emotional outpouring is to be permitted but he’s utterly captivated. So he has no active place to put it. His mind is being blown and she’s delighted. There’s also a detail which is one of those apocalyptic details when the father goes and rings the bell of this church just down the street which is curiously (as again in small towns of this kind—I mean it’s not a very small town—it is a small town) this is one signal to the populace that something terrific is happening: either the town’s on fire or the British are coming or something really cataclysmic has occurred. So he rings this bell, some say, at some early evening hour and people come running out and he points to the sunset. That would argue some continuity in the dispositions of the family.

The mother is a more complex figure and is the one who I guess, in some ways expectedly, both the daughters have various qualifications of. She is much less articulate. Emily Dickinson at one point rather belabors her for never having taught her to sew properly so that their clothes that they make themselves—again not arguing any poverty but just as a habit of the time—turn out not to be too well made because they never learned proper seamstressery or whatever it would be… Her letters, for example, to a particular friend of hers—she’s at Amherst Academy; again, Leyda’s book is very useful. The thing starts “Amherst, Sep. 2, Wednesday.” This is 1846, so she’s 16—no she’s 15 actually. From the Amherst Express Aug. 14: fall term opens at Amherst Academy “under the care of Mr. Leonard Humphrey AB assisted by Mr. James Humphrey in the English male department and Mrs. Elizabeth Adams in the female department.” Everything was sternly divided into males and females, but not hopelessly. Anyhow, her friend Abiah Root, she speaks, she’s writing to her about having been to Boston:

I don’t think that this is immensely pious and I can’t believe, despite the fact that those hundred and more years separate my secular thinking from her possibly still committed religious disposition, that is anything more than a lovely, characteristic wit of an intelligent young 15-year-old girl. And I love the way she’s teasing this far more serious friend: “I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ were I called to die”—it’s a rather absolute statement: “Pray for me, dear A. that I may yet enter into the Kingdom, that there may be room left for me in the shining courts above. [P.S.] Austin entered college last commencement. Only think! I have a brother who has the honor to be a Freshman! . . . I have altered very much since you was here. I am now very tall and wear long dresses nearly.” That’s terrific. I was really attracted to that person. Now she’s gone—this is 1847—and she writes to the same friend who’s now at a school in Springfield, Mass., which distance from Amherst is possibly twenty miles. And she in turn is gone to Mount Holyoke Seminary which is about nine miles from her home: “I’m really at Mount Holyoke Seminary and this is to be my home for a long year … It’s been nearly six weeks since I left home and that is a longer time, than I was ever away from home before now.” Again, I suppose what happens is that biographers say, “Wow, already it’s beginning, you know, she’s lonely, isn’t that awful.” I don’t think that’s such a remarkable emotion if you’re still living at home. Anyhow, I think I’ve known many children to have that very feeling:

I room with my cousin, Emily [Norcross—this is her mother’s sister’s daughter], who is a Senior. She’s an excellent room-mate and does all in her power to make me happy. [She’s also, as one finds otherwise, a very serious kid, very pious and very, you know, very devout.] You can imagine how pleasant a good room-mate is for you’ve been away to school so much. Everything is pleasant and happy here [sounds awful] and I think I could be no happier at any other school away from home. Things seem much more like home than I anticipated and the teachers are all very kind and affectionate to us. They call on us frequently and urge us to return their calls and when we do we always receive a cordial welcome from them.

I will tell you my order of time for the day, as you were so kind as to give me your’s. At 6. oclock, we all rise. We breakfast at 7. Our study hours begin at 8. At 9, we all meet in Seminary Hall for devotions. At 10-1/4. I recite a review of Ancient History, in connection with which we read Goldman and Grimshaw. At. 11. I recite a lesson in “Pope’s Essay on Man” which is merely transposition. At. 12. I practice Calisthenics and at 12-1/4 read until dinner, which is at 12-1/2 and after dinner, from 1-1/2 until 2 I sing in Seminary Hall. From 2-3/4 until 3-3/4 I practice upon the Piano. At 3-3/4 I go to sections where we give in all our accounts for the day, including Absence-Tardiness-Communications-Breaking Silent Study hours-Receiving Company in our rooms and ten thousand other things, which I will not take time or place to mention. At 4-1/2 we go in to Seminary Hall, and receive advice from Miss. Lyon in the form of a lecture. We have Supper at 6. and silent study hours from then until the retiring bell, which rings at 8-3/4. But the tardy bell does not ring until 9-3/4 so that we don’t often obey the first warning to retire.

Unless we have a good and reasonable excuse for failure upon any of the items, that I mentioned above, they are recorded and a black mark stands against our names …

My domestic work is not difficult and consists in carrying the Knives from the 1st tier of tables at morning and noon and at night washing and wiping the same quantity of Knives. I am quite well and hope to be able to spend the year here, free from sickness … One thing is certain and that is that Miss Lyon and all the teachers seem to consult our comfort and happiness in every thing they do and you know that is pleasant. When I left home, I did not think I should find a companion or a dear friend in all the multitude. I expected to find rough and uncultivated manners and to be sure, I found some of that stamp, but on the whole there is an ease and grace a desire to make one another happy which delights and at the same time, surprises me very much.

That is certainly drear. But again, ED is writing to her brother. This is December, this is her 17th birthday at this point; “I finished my examination in Euclid last eve and without a failure at any time. You can easily imagine how glad I am to get through with four books for you have finished the whole forever … I had almost forgotten to tell you what my studies are now—‘better late than never.’ They are, Chemistry, Physiology and quarter course in Algebra. I have completed four studies already and am getting along well. Did you think that it was my birthday yesterday? I don’t believe I am seventeen!” Miss Todd’s notes on conversations with Lavinia Dickinson: “Emily was never floored. When the Euclid examination came and she had never studied it, she went to the blackboard and gave such a glib exposition of imaginary figures that the dazed teacher passed her with the highest mark. There were real ogres at South Hadley then.” And so on and so forth. But my sense is, doing probably the very thing that I have such exception to others doing, that the density of circumstance, and the closeness that she’d had in Amherst is obviously very hard to leave: the family patterns, the siblings, and the closeness of friends. They had a group—they called themselves “the five”—they were very old-time cronies, and that group began variously to break up; Abiah Root’s going to Springfield, that was hard. There were certainly deep and particular affections and attractions, very consistent with any of our coming of age.

But there were kinds of questioning which were not simply symptomatic but were really, to my mind, a very insistent fact of her particularity. I remember, for example, one instance of a friend of mine in a somewhat like school, an Episcopalian school—I don’t imagine her saying this necessarily—but I remember we were being prepped for Easter, and being as it was an Episcopalian school, we were getting very benignly, but very particularly, the whole rehearsal of that. And I had one friend who was a North Carolina person, Dave Nichols, and I remember as we’d now been rehearsing this for something like two or three hours, him whispering in a loud mutter, “‘Why didn’t they hang the bastard?’ And I remember the minister just shook with outrage and irritation. Because it was true, he was to all intents and purposes without paternity and they could have hung him as well as crucified him. That kid would never be weirdly unreasonable but he would never accept something that was not explicit in its condition. This is Emily Norcross writing to Mrs. Porter:

And she does. And you must, if you have even a quick sense of her, you must obviously know that her imagination of this authority is intensive as probably any writer’s in the language. It isn’t that she won’t yield but she won’t yield what she knows and recognizes as existing for that which is abstract. I think that for my feeling one of the most reassuring and terrific aspects of her writing is that it never moves to a dislocated abstraction. By which I mean, it’s the extraordinary physical and sensual base of the language that I find extremely relieving. Whatever the rhetorical tone, I find it immensely attractive, etc., etc.

Then very just quick, the party ascends Mount Holyoke and registers in the mountain house register on Oct. 9, Tuesday, 1849 and the signatures are Miss Charlotte C. Haskell, Miss Lavinia N. Dickinson, Miss Caroline E. Haskell of Amherst Mass., Mr. Thomas H. Leavett of Boston, Mr. John L. Spencer of Amherst, Mr. Horace M. Smith of Amherst, Miss Emily Dickinson of Amherst, Miss Abbie N. Haskell of the Holyoke House, etc., etc. Again as ED reads her brother’s copy of Lalla Rookh by Thomas Moore, the Irish poet, and adds remarks to passages that interest her: “Who that feels what Love is here / Who that feels what love is here / All its falsehood, all its pain / Would for even Elysium’s sphere, / Risk the fatal dream again.” Then a little later, “I knew, I knew it could not last / ’Twas bright, ’twas heavenly but ’tis past / ever thus from childhood’s hour / I’ve seen my fondest hopes decay.” And finally . . . the one I was fascinated by: “Whose life as free from thought as sin / Slept like a lake til Love threw in / His talisman and woke the tide / And spread its trembling circles wide.”

One thing, and a kind of hopeful lunge toward responsible scholarship, which as I realize is beyond me forever, I thought I’ll track the word “circumference” because it’s such a delicious word in her use of it. It leads to all manner of pleasant associations with Shelley, for instance, all curious, all curious echoes. And it’s such a complex word of her imagination. It has to do with the emanating aura. And I was fascinated in reading where she says for instance, “My business is circumference.” It’s an endlessly specific word and all through the body of her work, it isn’t simply a word used in one particular time. It’s recurring and insistent. It has to do with her sense of the immanence. She says the Bible is a center, that which is experienced as an absolute contained, thus formally secure; that which has a center. But “my business is circumference.” To me, I could read it as everything from that immanence, from such a situation, but it had also for me an insistence upon relational patterns. I wanted to go into that in another talk. I thought this evening when Duncan McNaughton generously asked me what specifically I’d like to engage, just in a moment literally, I thought of proposing three titles and I thought this evening could be “The Girl Next Door,” literally the person who lives there also and who is as familiarly close as that and what would she have been, so to speak, in some imagination of her. Was she remarkably distinct? Yeah, she was. Her aunt, for example, with whom she stays—her mother after Lavinia’s birth is ill for a time (not too significantly) but her mother is characteristically ill quite frequently. As again was common in that time and place. But in any case, (as was Emily also) she leaves Mount Holyoke because of illness, never quite specified. I don’t think it’s simply neurasthenic but it could have been anything like a persistent bronchial pneumonia or something like that. There’s much of that in that time and place. Again, if one isolates her from her context, the insistent preoccupation with physical death might seem morbid. It’s such a frequent event. I mean, the endless rehearsal of dying, the endless fact of dying is very common. If one reads simply the accounts of the family pattern, characteristically the families are having, women are bearing as many as ten to twelve children, of whom the characteristic survival would be five or six. So children specifically are dying very frequently. But elders too. And very often the young, in the sense of teenagers or persons in their early twenties, so it’s a very familiar event.

Also, I was struck by the fact that papers, again of that period (there’s an Amherst paper; I think there’s even at one point two; there are several local, really local papers; there’s also the paper that the person becomes a very close friend indeed—Samuel Bull’s Springfield paper becomes a paper of real national authority), these papers report local events in a very old fashioned way by saying so-and-so’s been ill lately. You know—things of that sort. There’s no dramatic “Father Of Two Kills Five”—that kind of thing. It’s “Mrs. so-and-so is recovering from a long illness and we are pleased to wish her well.” The very familial and local sense of reality.

So what I did want therefore to emphasize was simply that the father, for example—when he’s off on various trips to Boston or a similar place—will write what might seem a bit stiff but the fact, thinking of a few of our fathers and what not—now we substitute Ma Bell for a note—but you hear, it’s the old-fashioned saying, “Give Johnny a hug and a kiss and tell him to be good and not make trouble at school. Or tell him I’m pleased to hear he did, you know, this or that or had a good time at Johnny’s house,” that sort of thing. The father was extraordinarily resourceful and responsible in that way. He brings home the characteristic books or presents of that interest and time. His letters to his wife certainly were marks of real affection and care. He’s certainly a domestic man without the least exception. He cares very much for his family. He has the confusion consequent in any male behavior, given a form that’s didactic about the ways in which a male is supposed to act. But I don’t see him as an overbearing or difficult father. It just doesn’t make sense to me. There is no remarkable contest, for instance, between him and his eldest son, which would be a classic place to have it register. The oldest son in fact is a very warm and affectionate presence: Austin. Austin’s difficulties begin with marriage and one doesn’t ever really know what became so curiously bleak. His letters, by the way, are very interesting, the letters he writes to Mabel Todd. They are incredibly intense. Lavinia was the more sort of sensually playful and accessible of the kids with a wry, pert tongue. I had an Aunt Bernice who must have been like her. She fronted, so to speak, more comfortably for the kids, for her sister. But it’s Austin and Emily who had this very playful and engaging affection for each other. And Emily much misses her elder brother when he leaves the house to go about his life and says there’s no more “hurrah”—she has some phrase like that—there’s no more bustle, jokes, funning with father, sort of pleasant teasing and punning. She feels that—yeah, she much misses the humor. So I don’t get a sense of an awful, stern, rockbound household.

Let me just read a couple of bits. This is 1850. May 7 she writes to the same friend, Abiah:

Then she writes (this is the next day):

Then on May 7, she writes again:

On the lounge asleep lies my sick mother, suffering intensely from acute neuralgia, except at a moment like this, when kind sleep draws near, and beguiles her,—here is the affliction.

[…]

I have always neglected the culinary arts, but attend to them now from necessity, and from a desire to make everything pleasant for father and Austin. Sickness makes desolation, and the day dark and dreary; but health will come back, I hope, and light hearts and smiling faces.

[…]

I presume you have heard from Abby and know what she now believes—she makes a sweet, girl christian, religion makes her face quite different, calmer, but full of radiance, holy, yet very joyful. […S]he is certainly very much changed.

I want to read a sequence of poems, not only as a chronology but as some sense of the way she’s moving at these various points. I do think that she’s a poet who is most usefully read—the text of this book, they say there are one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five poems in the Collected Poems—they’re an extraordinary range to read and to see the echoes and patterns and intensities that gather. Again, something that I think really beguiled me, and confused me more accurately, reading her primarily was that I was reading the classical anthology contexts and she is a poet who’s not so much been necessarily misused by editors, and one will make judgments as one cares to. But because one was always getting selections and pieces and designs, the effects of this edition (Thomas Johnson, ed., Harvard University Press, 1958) were remarkable, because one began to have at least some sense of an active passage of incredible genius. And could see its economy and its gathering and its power and its power and its resonance. Just incredible. There’s a time, for example, about 1862, that period—about 1860 to 1863 or 4 or 5—around 1862, when she’s writing at least a poem a day. She’s writing extraordinarily. And the most incredible authority. She’s just what—31, 2 at that point. That’s of course the point where the critics want to say she must have had a disappointed love affair. I think it’s far more simple than that. That’s when she goes for broke and writes Higginson. That’s when the authority of her ability must have utterly been possessed, possessive… And that’s of course the time too when she begins to make decisive changes in her whole proposal of herself to the world.