He dies one year after my grandfather’s birth, it is 1919, leaving my great-grandmother to raise a family alone.

They live in Springfield, Massachusetts.

It is the Prohibition. The point is: they live through this untimely death.

At this point in the story, the United States government has banned the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. Celia, my great-grandmother, becomes a bootlegger.

This story is about survival: it’s about family, but it’s also about home.

In this story, my grandfather, Jake, is fatherless. His mother makes whisky in the bathtub. He’s told this one before. When I ask him to repeat it, he does, but there’s nothing to tell. Jake and his brothers deliver the whisky to “kitchen dives,” makeshift bars in nearby homes and apartments. The cops turn a blind eye, I’m told. As my grandfather, child of eight or nine, passes through the neighborhood, banned substance in hand, an Irish cop says the Yiddish words meaning “carry it in good health,” acknowledging his labor in moral if not legal terms.

My great-grandfather’s name is Wolfe. He owns a grocery store in Springfield, Massachusetts. His American name is William. He dies of an illness which today could be easily cured. What kind of person was he? The kind, says Jake, who gives food to those who can’t afford it. “Sound like anyone?” my grandfather says, meaning he believes, though he’s never owned a grocery store in Springfield, Massachusetts, though he has no memory of his father, he shares this quality of kindness with the man.

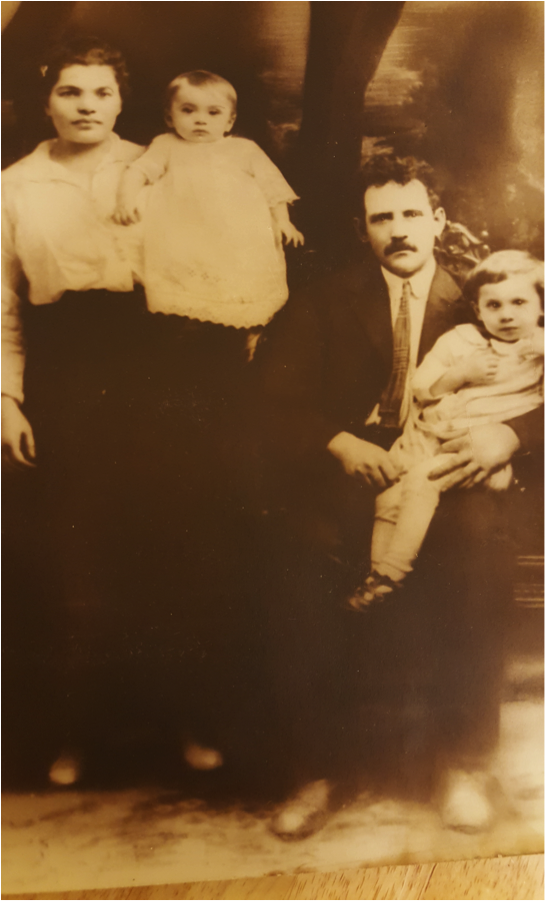

In my version of the story, there’s a photograph. This photo hangs on my grandfather’s wall. It’s of his mother, father, and two brothers, Sam and Shimmy, who’s just a baby. Wearing a white gown, Shimmy hovers in ghostly maternal embrace. I’m haunted by his expression, which I’ll simply call devout. His eyes are penetrating and deep. He seems to know something about me I’ve yet to understand as he stares ahead with preternatural calm. I feel observed–in the religious sense–that my life is merely a ceremony through which this gaze moves. I feel this even when I’m away from the image, even at moments I’ve forgotten it exists.

My grandfather is absent from the photograph. He wasn’t born yet. In my mind, his absence is joined with the figure of his dad. This is the picture’s second ghostly embrace. Two phantoms, one present, one past, caught in the recursive motion of time the image occasions for me. When I ask Jake what he sees in the picture, he says: “Let’s face it. I didn’t have a father.” This is not not seeing, I think. This is a foundational vision of loss. In this way, his father’s absence is present. In this way, homelessness is home.

I understand this last part as I investigate the story of Cotopaxi: When fifty Russian Jewish refugees arrive in 1882 to create an agricultural colony, instead of the houses they’d been promised, they find “eight rudely constructed cabins, about 16X20 or smaller, double boarded with tar paper.” In other words, the settlers rediscover their homelessness, which must seem built into the hidden architecture of history, geography, time.

Hide and hide, both noun and verb, are among the etymological associations for the word house. The first, “the skin of an animal tanned into leather,” means a covering. The second, the verb, suggests concealment. If a story is a covering for the events it describes, what it conceals it reveals. Narrative is a shelter, but a porous one. Another association is hoard, coming from the Old Saxon hord, meaning “hidden inmost place.” The story has the ability to stash away as it exposes. Often it does both at once.

“They had no doors or windows,” writes Flora Jane Satt of the settlers’ houses, “nor even the jambs or frames into which such might be easily fitted.” These buildings were as empty as the utopian dreams that lead these poor refugees to Colorado. A false narrative of a promised land in the American West results in the colonists’ very real arrival, but prolongs their homelessness, as the story goes, as its frame explodes into historical time, disappearing over the mute horizon of its telling.

Each of the settlers’ houses is a single story: “double boarded, with tar paper between them…They contain three rooms and a kitchen, with a stove and cooking utensils.” Framed this way by Julius Schwarz, an attorney for the aid society that financed the colony, there’s a sense of building toward its future rather than the immediate collapse they must have experienced on arrival, a collapse both literal and metaphorical, fictive and factual.

A single story moves into others. Informs and intersects. Unsettles and uproots. I understand this, for example, when I read an article about recent US immigrants arrested for selling banned substances. Their story is not that of criminals, as the article suggests, but that of family and survival, though there’s no Irish cop to wish them luck along the way. This is how I know, for example, when I see images of families in Gaza sifting through the rubble of demolished homes, I am witnessing the hellish habitation of an inverted historical landscape in which one people visit their traumatic history on another in the form of atrocities committed against them forever. In this way, one’s narrative of survival can be another’s nightmare. One’s home, another’s exile.

Two summers ago, I passed a pro-Israel rally in downtown Denver. A white, Jesus-loving politician delivered an Islamophobic speech on the steps of the capitol. Across the street was a counter-demonstration of Palestinians. Feeling at home in neither camp, I watched equidistant from rally and demonstration. Later, I wrote the following poem. As a way to give form to my doubt? As political equivocation? As counter-counter protest? Against what?

On the other, people cover their faces in fake blood to represent

the blood of stateless brothers and sisters. I think of a Pierrot Le

Fou. When Jean-Luc Goddard is asked why his film contains so

much blood, he says: “Not blood, red.” When we talk about “real

time” we mean we’ve glimpsed the idea of a present as it approaches

at the speed of the image the fact of its having been. So the moment

works backwards to itself. And in the shouts of the protestors,

in the eyes of passersby, that fake blood is not converted into real

blood, but its redness forms the face of a storied violence.

When I passed city hall after the rally ended, two groups of young men, one Jewish, one Palestinian, confronted each other. Each side taunted with shouts and chest-thumping. At this point, it seemed more about a misguided masculinity than the politics of nationhood. I wanted to intervene, to shame the Jews, but it broke up, each side waving their flag as if to return to the root of the conflict, having covered no ground. As with the right-wing politician, I think regarding these Palestinian men, and even, to an extent, regarding the Jews: We might be neighbors. We might pass each other on the street every day. We might be friends. But we’ll never live in the same country, not quite.

In this way, war and democracy, peace and death move through our quotidian lives. As a person moves through the rooms of a house. As a memory of home moves through the mind. I remember one day at my grandfather’s. He notices the holes in my sneakers and hands my mother several bills. “Buy him some new shoes,” he says. “I can’t stand to see that,” meaning the holes, into which he reads the continuing narrative of his early poverty. My grandfather is shamed by the thought that people might assume we can’t afford a new pair. It takes me years to understand this fact. It’s a fact outside of fact, one that frames the narrative into which it’s absorbed. His poverty has followed him into this moment, into family and economic mobility, through war and marriage and birth and death. Like a room he can’t leave. Like the walls of a house threatening to collapse around him at any moment.

The plot thickens: The settlers thought they had title to the land at Cotopaxi, but “[w]hen they prepared to depart the county,” Satt writes, “they checked with the county clerk in Canon City and could find there no record whatsoever of any such deed…They had simply been ‘squatters’ or perhaps at best, ‘tenant farmers.'” In other words, the story hadn’t changed. The colonists were again dispossessed. One man, Ed Grimes, walked 150 miles to Denver to make his home. “[Cotopaxi] was the poorest place in the world for farming,” he said 60 years later, “poor land, lots of rocks and no water, and the few crops we were able to raise were mostly eaten by cattle belonging to neighboring settlers.” This seems to contradict Schwarz’ newspaper column of 1882 in which he writes: “Every head of a family and several single men own a house, completely furnished, wagons, cows &c.” In his report on the colony to the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society that same year, he adds: “Where these are facts, no theories are needed. The argument of facts conquers all other arguments. The facts are that the Colony in Cotopaxi is a success.” This sounds less like a statement of fact than an attempt to conceal a hole in the plot. A theory is a gathering of facts arranged to represent a worldview, but the story is often who is theorizing and to what end. Not what these facts tell us but what they can’t—tiny, inarticulate ghosts of time wandering forever back and forth.

The fact is the settlers squandered three years on Saltiel’s property when they could’ve filed as homesteaders on nearby land. The Homestead Act of 1862 allowed individuals over 21 years of age to freely settle 160 acres. One just had to follow the steps: put in an application, improve the land, and, at the end of five years, file for deed of title. But mine is not a story as linear as the workings of the United States federal government. I won’t impose linearity on a story that exists so far outside its telling. In other words, I’m no historian. I want language to speak itself into secret relation with the past.

“Although counted as Russian subjects,” one historian writes, “the Jews existed apart…a nation within a nation.” In the 19th-century Pale of Settlement, my ancestors wandered the desolate landscape between alien and citizen. Celia, for example, for whom the pogroms of 1905 would’ve been a main plot point in her departure. For the Cotopaxi settlers, it was the pogroms of 1881 following the assassination of Tsar Nicholas II that proved they’d never gain true personhood. “For the Russian Jew,” writes the historian, “a dead neighbor, a raped daughter, a burned home brought direct confrontation with the tragedy that was his existence.” Substitute “Palestinian” for “Jew,” and we can recognize a territory occupied today by the same ancestral fear: “They’re won’t stop till we’re all dead!” Not only is this past not far behind, it’s often far ahead. This occurs to me when a friend mentions a recent trip to Germany made by her aunt, a woman who’s all but renounced her ethnic and religious identity. In the airport bathroom, the fire sprinklers are transformed in her mind into death-spewing gas valves. She screams, panics, runs for her life. It occurs to me, too, when I think of my father’s high school job at a club that did not admit Jews. One day on the golf course, he is targeted by a group of boys, who steal his prized hat, which he’d bought proudly with his earnings. How could I fail to understand this as family history inseparable from my own?

Some stories are so potent they carry through the generations. L’dor vador. Like those of childhood. For example, perhaps because of his early “difficulties” with alcohol, my grand-father doesn’t drink; neither does my dad. In this way, the past imprints its negative on us, telling us things it hardly permits us to understand. These things manifest as thoughts, actions, behaviors. Our very being provides the details of a story we don’t know and can’t tell.

Maybe Jake’s silence about his mother is a side effect of this phenomenon. Even Celia would’ve been eligible for land under the Homestead Act. My grandfather shrugs when I ask about her. Only since taking on the Cotopaxi project have I understood this silence as protection against the struggles of the past rather than the refusal it seems. In this silence, I’m sheltered but shut out.

One fact my grandfather shares about his mother is that she alone among the older generation is excited to gain her citizenship, which enables her to vote, a right denied our family in Russia. US citizenship is also the first requirement of the Homestead Act.

Can we think of a citizen as house merged with home in human form? The English home has the same Indo-European base as the classical Latin civis. From the Old Dutch, hiem, it means homestead. In the Old Saxon, hem, there’s the suggestion of homeland. At the root of the English, the civic, historical, geographical, and personal intersect. Deprived of home in every sense, it’s easy to imagine the Cotopaxi colonists settling into a narrative of their dispossession. When one of them says the word home, does utterance become a utopic project, a non-place in which their journey to Cotopaxi meets a hoped-for destination? Shelter from the storm.

This reminds me of a story. One night, years ago, my family gathers at my cousin’s house. I say gather rather than get together, for example, because the root of the former is taken from the Old English gadrian, which means to assemble, enabling the suggestion of a gathering not just of people but of the past itself. Jake and Roz, my grandmother, do the telling.

Listen:

In the winter of 1991, it starts to snow in Hartford, Connecticut. Everyone at my cousin’s house has heard the story. The point is the telling, not the story. In the story, my grandmother goes to the store. When a some time passes and she hasn’t come back, Jake goes looking for her. He drives down Carlyle Road, turning left at its sloped bottom. Due to icy conditions, he loses control of his car. A second car turns the corner at this exact moment. This car also loses control. They collide. No one’s injured but thousands in damage is done to both vehicles. “It’s you,” my grandfather says my grandmother yelled, jumping from her car. “It’s you!” I can see her pointing as at the twist in the narrative. Besides justifying an otherwise boring story to the listener, this irony is meant to describe my grandparents’ relationship. Isn’t this irony the nature of family? it asks. To this question, we would all answer, Yes. Family is a form of irony into which chance and chaos freely enter. Here the story and its telling are not different but not quite the same.

Like I said, though, it’s the telling, not the story. I’ve told the story but I haven’t told the telling. At this gathering, Jake and Roz are surrounded by family members who constantly interrupt. These interruptions are absorbed into the structure of the story; they create narrative form. They are part of the story and they are commentary. Its telling thus becomes a mode of family left open to chance, chaos, and interpretation. When cousin Alan interrupts, for example, to comment that my grandmother, despite the atrocious weather, felt a nearly sexual compulsion to purchase hamburger meat for eight-eight cents a pound, the story’s context is expanded to include this bizarre knowledge of her character, bringing it back to the moment of its telling, changed and new. The story, thus collapsing under the weight of this commentary, is like the walls of a house demolished to add rooms for each new arrival. If each interruption is a room in this house, the endless comments make it habitable for all.

There’s even a surprise ending to the surprise ending that arrives a decade after the fact. One day, cousin Bernice visits a mechanic. This mechanic wants to tell her a story. He’s got a great story, he tells her. “You’ll never believe it,” says the mechanic, who proceeds to give an account of my grandparents’ accident. Here, as in the Russian mir, meaning home, which carries the sense of commune and community, the telling is collectively inhabited. Everyone’s invited. Bernice’s laughter confirms her belief and makes her part of the story on which it comments.

But what’s the relationship of the story to history? Can language become home? “The houses are so poorly constructed that on such a night as we saw them, the wind howling violently, the little shanty almost succumbs.” This is from the 1882 Kohn-Wirkowski report on Cotopaxi. The house’s shoddy construction makes for a compelling narrative of persistence and misery. But a poorly told story can be a good one, a history not of the event it describes but of the telling, opening it to the teller in ways inconceivable to those who slogged it in real time. In this way, it’s a negotiation between living and dead. Every story’s a ghost story. I’d like to imagine its form in relation to the Latin structura. Not a pre-fabricated linguistic dwelling but a process of telling. A linguistic phantasm lodged in the facts it presents. A story is a history in that it fails as it succeeds, welcoming the listener refused entry to the past it evokes. It is, in other words, a death: joyful, inconsolable, out of time.

I think of the stories Jake can’t tell about his father. If the non-stories of William’s non-existence shaped him, because he’s shaped me, they’re profoundly my own. If Jake believes he shares with William his charitable impulses, I must measure myself against this standard, however dubious. When I sit on a park bench in Denver in the middle of April, crossing my right leg over my left and letting it hang exactly as Jake does, I think of Etel Adnan on her beloved Mt. Tamalpais: “Its form is the substance of what we are. When I make a gesture, casually, I draw it in the air.” Is this relation or residence? I wonder, settling into the bench. I am separate but indivisible from this man who turns ninety-eight this year. In this casual gesture, we intertwine. When Jake dies and I cross my legs, when he no longer exists to do so, will I inherit this form or inhabit it? Am I image or substance? Story or teller?

When I think of my grandfather’s death, it is as a destination located so deeply in my being it becomes a dwelling place both phantasmic and real, fact and fiction. For some reason, I picture the walls of his house, which he sold several years ago. As I was clearing the last of his things from the living room, I remember getting a moment’s look at my grandmother’s picture on the wall—Roz, who’d died ten years earlier. When I looked again, the wall was empty. Her picture had been removed, who knows how long ago? What I’d seen was an instant of personal history cross-hatched with its loss. A memory out of time; a ghost. The image of my grandfather’s death, though it exists in an unknown future, is habitable for me as memory. This is Barthes’ punctum as aporia stabbing crazily at abode. I see this image as clearly as I read its litany of refusal.

Returning to the photograph of my grandfather’s family, the one from which he’s absent, I’m drawn to Celia. The texture of her hair is heartbreakingly real. I want to touch it. This desire becomes nostalgia for a person I never met. Celia died before I was born, so it’s the image of an image I visualize as I consider this woman who fled Russia with no hope of seeing her family again. Do I even have the right to think of her as a person when, for me, she’s an image tucked away in a corner of the room? There’s a narrative here I can’t quite grasp. When I look her up in the 1963 Massachusetts City Directory, she’s listed, 45 years after his death, as the widow of William Fagin. I wonder when his death transcended loss to become another fact of life, another story told to brace herself against her struggles. Or where, in the course of raising his three children, this fact released her to its reality, becoming the ghost of what must’ve seemed a previous incarnation.

**

I find a picture in my parent’s basement. Who’s in it? No one knows. My father thinks it might be his grandparents on his mother’s side. On back there’s a note: March 1945. In the photograph, two elderly people, a man and woman, stand unnaturally erect against a wall. This gives the picture a feeling of formalness and occasion. The man’s hands are at his side, the woman pushes an arm through his elbow. Moldering slowly over the years, much of the image is engulfed by a whiteness that seems to spread as I look. It’s like the frame is being eaten by a light from beyond, one that will some day overtake it. At this point, the heads of the man and woman are nearly invisible. They seem to disappear, retaining a vague outline. I can just make out the look of excitement on the woman’s face. If my father’s right and these are his grandparents, they’re likely waiting for the return of their son, Eddie, from the war. Behind them are two words big as life, which I can read only by gestalt effect. Demolished by decades of poor storage, the sign on which they appear is both legible and illegible, there and not. “WELCOME HOME,” it says. Welcome home. Welcome home.

Adam Fagin’s recent chapbook is THE SKY IS A HOWLING WILDERNESS BUT IT CAN’T HOWL WITH HEAVEN (Called Back Books 2016). His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in New American Writing, Colorado Review, Boston Review, The Seattle Review, Volt, Fence, and many other journals. He is working on a book of lyric essays about family, home, the intersection of personal and public history, and Cotopaxi, an abandoned 19th-century Jewish agricultural colony.

Adam Fagin’s recent chapbook is THE SKY IS A HOWLING WILDERNESS BUT IT CAN’T HOWL WITH HEAVEN (Called Back Books 2016). His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in New American Writing, Colorado Review, Boston Review, The Seattle Review, Volt, Fence, and many other journals. He is working on a book of lyric essays about family, home, the intersection of personal and public history, and Cotopaxi, an abandoned 19th-century Jewish agricultural colony.