Zodiak (1) |

Zodiac (1) |

|

Ujëra, ujëra, ujëra,

popuj shirash, fëmijë pikash, të palindur prej avujsh, amfora hyjnish me baltë të pjekur nga muskujt e njerëzve, poçe lypësish bërë nga balta e eshtrave të Cezarit, shpirtin ma rrëmbejnë ujëvarat dhe ato vrapojnë e lënë pas formën time të zbrazur. Demonët e lumenjve klithin, askush nuk i di rrugëtimet e ujërave të nëntokshme, kafshët e lotëve dalin nga çarqet e qepallave, dua të zjej zjarrin brenda një ene uji, rubineti i çezmës në kuzhinë pikon si bibilushi i një Erosi. Do të më vrasë dashuria, do të më verbojë mirëbesimi, do të më mallkojë poezia! Oqeani mbulohet me një epidermë njeriu. Shoh në ëndërr vetveten, pra, gjumi është pasqyrë e rëndomtë, fijet e dëborës janë eshtrat e të vdekurve para pesë mijë vjetëve, përjetësia ka rënë në dashuri me vogëlsitë e mia të vdekshme. Mendimin e padukshëm si ta bëj pikturë të mrekullueshme? Ylberi është ombrella e harruar e Van Gogut te karrigia e një kafeneje bohemësh në Paris, engjëjt me reumatizëm lagen e dridhen në shi, kudo kërcejnë dhe dalin bretkosat e Voltës nga mëngët prej prestigjiatori të rrufeve, bretkoca, që kuakin dhe bredhin në kompjutera, te mumjet e faraonëve të Egjiptit. Gjithësinë e kap ngërçi, nga paraliza erërat janë si statuja të copëtuara. Ku ta kap peshkun, që ka në bark shishen e një mesazhi të një Krishti fëmijë të mbytur? Mijëvjeçarë, martohuni te emri im! O, Talesi i vjetër i Miletit me pikën e ujit ftillëzonte gjithçka. Uji qe fara dhe plaçenta e botës. Vetë njeriu është më tepër ujë, njeriu dhe peshku s’janë raca të ndryshme. Te pika e ujit shihni vetë Talesin mikroskopik me gjymtyrët lëvizëse prej bakteresh, këtu janë popullsitë e panumërta, banorët e ardhshëm të Marsit alienët e Udhës së Qumështit. Pika e ujit është porta për të gjithë e të lindurve dhe e të munguarve. Shkretëtirat vijnë me kocka, devetë e djersës i hëngrën palmat, zogjtë u mbyllën te vezët e thara të oazeve, ajri pa erëra është si skeleti i hierogliftë, vdis dhe ti oshënar i kokrrizave lakuriq zhvishu dhe nga trupi. E mbush një Aristotel prej amfore |

Water, water, water:

torrential people—droplet-children from still-pregnant clouds: amphorae of the gods molded from mud, shaped by the force of Man. Beggars’ pots made from the clay of Caesar’s bones. How my spirit flows out of me in a waterfall, running forth, leaving behind my empty form. Demons of howling rivers— how little we know of the weavings of underground streams, the beasts of tears released from the traps of eyelashes. I want to boil fire inside a pot of water— the kitchen tap keeps dripping like Eros’ little prick. Love is sure to kill me, good will is sure to blind me. Poetry is sure to curse me. A whole ocean is sealed inside a person’s skin. I see myself in a dream— thus, sleep is just an ordinary mirror, and snowflakes are the bones of the dead from five thousand years ago. Eternity has fallen in love with my tiny, mortal self. How can I transform my blind thoughts into a spectacular image? A rainbow is an umbrella Van Gogh left behind on a chair in some bohemian Parisian café. Rheumatic angels are getting soaked in the rain, and the Volta’s hopping frogs emerge in a flash, as if from a magician’s sleeve. Millions of frogs croaking and wandering inside our computers—mummies of the Egyptian pharaohs. This All-Encompassing is getting cramped, and the paralyzed wind is like a crumbled statue. Where can I catch the fish that still holds in its belly the bottled message of a drowned Christ child. Millennia— marry each other inside my name! O, Old Thales of Melitus—for you, a single drop of water made everything clear: water was both the seed and the placenta of the world. Man is water— thus a man and a fish can’t be all that different from each other. In a drop of water, we find Thales himself—microscopic, his thrashing bacterial limbs—. Here are the human multitudes, the Martians of the future, the aliens of the Milky Way. A drop of water is the portal of all who have been born and all who are yet to come. Deserts will arrive to cover our bones, sweaty camels will make short work of palms, birds will seal themselves in the empty egg shells of oases. The windless air is a hieroglyphic skeleton. You naked eremite of these grains, die!— slough off your body! I can fill the amphora of Aristotle |

Notes:

1. Jeronim (or Girolamo in Italian) De Rada (1814-1903), one of the most famous Arbëresh lyric poets. The Arbëresh are the descendants of Albanians who resettled in southern Italy after the Ottoman invasion of Albania in the 14th century. back

2. Epidamnus is the name of an ancient Illyrian city founded in 627 BC in what is now Albania. It was subsequently colonized by Greeks from Corinth. Later it became the Roman city of Dyrrachium, then the modern Albanian city of Durrës. back

3. The adjective “Taulant” refers to the Illyrian tribes who inhabited the coastal lowlands of central Albania. back

4. Dyrrachos—one of the indigenous (pre-Greek) founders of what, today, is the city of Durrës—was said to be the offspring of a union between Poseidon and his mother, Melissa. back

5. Dyrrahu is the ancient indigenous name for the city of Durrës. back

6. Redon is the name of the Illyrian god of water and the sea. back

7. Ndre Mjeda (1866-1937), an important Albanian lyric poet and Catholic theologian. back

8. Ali Pasha of Tepelena (1741-1822), Albanian ruler who at times acted rebelliously and defiantly toward the Ottoman powers of his day. When asked by Sultan Mahmud II to surrender for beheading, Pasha famously replied, “My head [. . .] will not be surrendered like the head of a slave.” After two more years of fighting against the Turks, Pasha was indeed beheaded. He appears, at least semi-fictionalized, in Byron’s Childe Harold and Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo. back

9. Grammata is a small bay on the Karaburun Peninsula, in the south of Albania. The high rocks surrounding the bay are full of inscriptions in Greek, Latin, and Albanian going back to antiquity. back

A BRIEF NOTE ON MOIKOM ZEQO & ZODIAC

by Wayne Miller

Zeqo’s poetry career began in the late 1960s, when Albania had recently severed its ties to the Soviet Union because of Krushchev’s divergence from Stalin’s hardline legacy. In that particular moment, Albania’s communist dictator, Enver Hoxha, had—surprisingly—sided aesthetically with a number of younger, free-verse poets who were resisting the prescribed aesthetics of socialist realism. Zeqo, then in his early 20s, was one of the poets who took advantage of this aesthetic “opening.” From 1970 to 1974, Zeqo wrote the poems in I Don’t Believe in Ghosts (BOA, 2007; in my translation—in Albania, the book was called Meduza), which not only experimented aesthetically but also pushed back, however limitedly or indirectly, against the rigidity of Albania’s cultural isolation and political bureaucracy.

As it turned out, Hoxha’s support of younger, nontraditional poets was partially a form of inviting “criticism from below,” and many of the poets in Zeqo’s cohort were subsequently punished through imprisonment, suppression, or, as was the case with Zeqo, “merciful” exile from Albania’s cities. Most were also stripped of their posts within the structure of the Writers Union. (Zeqo, for example, lost his editorship of Drita [The Light], Albania’s official literary journal at the time.) Meduza was suppressed and remained so until 1995. After his period of exile, Zeqo published a couple “safer” books of poems and developed a successful career as an archeologist. In fact, he was one of Albania’s first undersea archeologists. After Hoxha’s death, toward the end of what could be considered something of an Albanian version of a “glasnost” period, Zeqo served as Albania’s Minister of Culture. When the communist system collapsed he directed the Albanian National Historical Museum.

At the end of the 1990s, Zeqo wrote the book Zodiac (“Zodiac [1]” is the opening section) with the turn of the millennium in mind. Though the overarching frame of the book is a sequence of poems based on the zodiac, that summary doesn’t offer a particularly accurate picture. As an archeologist, classicist, and historian, Zeqo’s interest in the zodiac is primarily historical and cultural, not astrological (except perhaps in a playful, self-ironizing way, such as in the closing poems of the book, which are all called “Predictions”).

When Albanian communism fell, Zeqo decided to stay in Albania, though many other intellectuals with international connections left to avoid the socioeconomic chaos and internecine conflicts that have complicated Albanian politics and cultural life ever since. In many ways, Zodiac is a love letter to Albania, a heartfelt explanation of why Zeqo continues to be drawn to and inspired by the ancient cultural and historical roots of his country and the larger Adriatic region—and, thus, why he decided to stay. At the same time, Zodiac is also deeply concerned with the complexities of a technologically driven 21st century. Zeqo knows that his love of classical history puts him at odds with the dominant culture of contemporary Albania and Europe, a fact he wears with both pride and self-deprecating humor. Ultimately, more than anything else, Zodiac addresses Zeqo’s mortality, assessing the overall legacy of his life, which has been multiply dedicated to a deeply important—though long-neglected—historical locus situated between ancient Rome and ancient Greece, as well as between Europe and the Muslim world.

The resulting combination of these concerns and the poems’ formal layout presents—at least to my mind—a kind of playful, surreal, historically referential Albanian Duino Elegies. This seems to me particularly the case when I consider Zodiac in relation to the shorter, more concrete—though often quite surreal—work in the earlier I Don’t Believe in Ghosts. Overall, Zodiac is both ecstatic and self-ironic, driven by Zeqo’s overwhelming desire to connect with a readership, with literature, and with the future—though that desire seems set to be thwarted by the tiny audience there is in the world for both his language and his historical interests. The more time I spend with these poems, the more brilliant, complex, and ultimately moving I think they are.

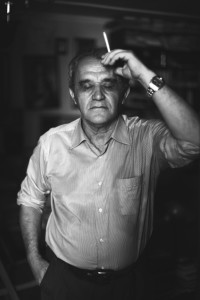

MOIKOM ZEQO, born in Durrës, Albania, in 1949, is the author of more than a dozen books of poetry and fiction, as well as numerous monographs on Albanian history, literature, and culture. His book Meduza (published in English as I Don’t Believe in Ghosts, BOA, 2007) was suppressed in Albania from 1975-1995 and only appeared in print after the Communist collapse. In the mid 1990s, Zeqo served briefly as Albania’s Minister of Culture, and for many years he directed the National Historical Museum in Tirana. An archeologist by training, Zeqo lives in Tirana and works as a writer and journalist.

MOIKOM ZEQO, born in Durrës, Albania, in 1949, is the author of more than a dozen books of poetry and fiction, as well as numerous monographs on Albanian history, literature, and culture. His book Meduza (published in English as I Don’t Believe in Ghosts, BOA, 2007) was suppressed in Albania from 1975-1995 and only appeared in print after the Communist collapse. In the mid 1990s, Zeqo served briefly as Albania’s Minister of Culture, and for many years he directed the National Historical Museum in Tirana. An archeologist by training, Zeqo lives in Tirana and works as a writer and journalist.

ANASTAS KAPURANI is the author of The Myth of Lasgush (Upfront [UK], 2004), a critical study of the Albanian poet Lasgush Poradeci. Kapurani lives in Athens, where he teaches for the London Institute City and Guilds program.

WAYNE MILLER is the author of four poetry collections, most recently The City, Our City (Milkweed, 2011) and Post- (2016; forthcoming), and he has translated two books by Moikom Zeqo: Zodiac (Zephyr, 2015; forthcoming) and I Don’t Believe in Ghosts (BOA, 2007). In the fall of 2014, he will begin teaching at the University of Colorado Denver, where he will serve as Managing Editor of Copper Nickel.