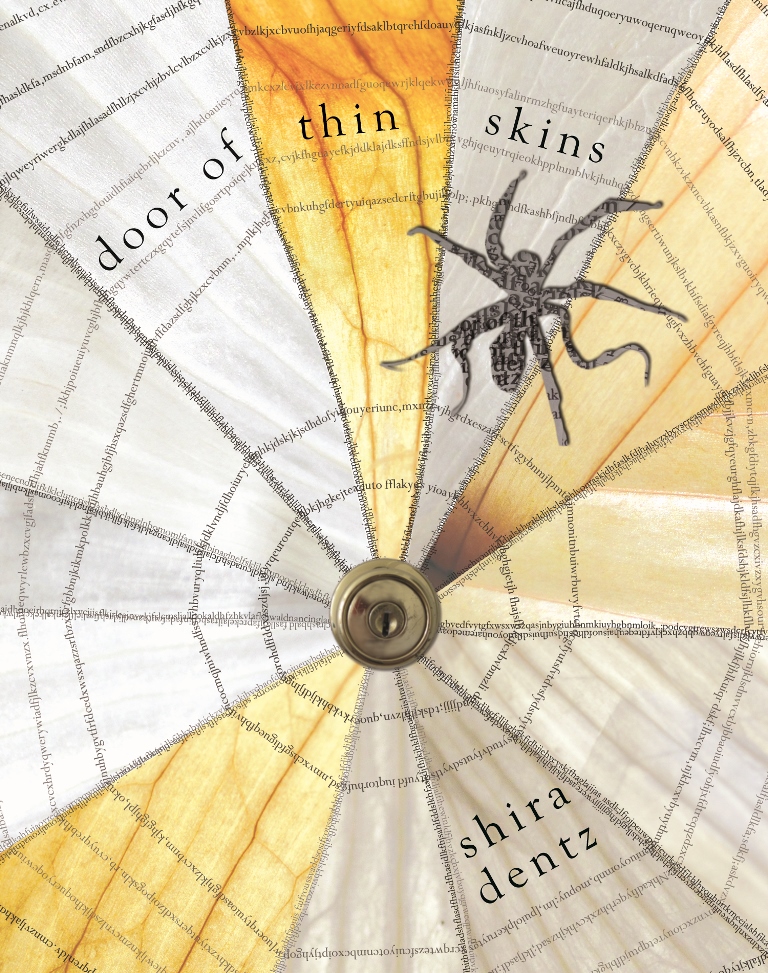

Shira Dentz is the author of two books, black seeds on a white dish (Shearsman) and door of thin skins (CavanKerry Press), as well as two chapbooks, Leaf Weather (Shearsman) and Sisyphusina (forthcoming from Red Glass Books). Her writing has appeared in many journals, including The American Poetry Review, The Iowa Review, and New American Writing, and featured online at The Academy of American Poets’ website (Poets.org), NPR, Poetry Daily, and Verse Daily. Her awards include an Academy of American Poets’ Prize, the Poetry Society of America’s Lyric Poem Award and Cecil Hemley Memorial Award, Electronic Poetry Review’s Discovery Award, and Painted Bride Quarterly’s Poetry Prize. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she has a PhD in creative writing and literature from the University of Utah, and was writer-in-residence at The New College of Florida in spring 2012 and 2013. She is also Drunken Boat’s Reviews Editor. Find her online at www.shiradentz.com.

Shira Dentz is the author of two books, black seeds on a white dish (Shearsman) and door of thin skins (CavanKerry Press), as well as two chapbooks, Leaf Weather (Shearsman) and Sisyphusina (forthcoming from Red Glass Books). Her writing has appeared in many journals, including The American Poetry Review, The Iowa Review, and New American Writing, and featured online at The Academy of American Poets’ website (Poets.org), NPR, Poetry Daily, and Verse Daily. Her awards include an Academy of American Poets’ Prize, the Poetry Society of America’s Lyric Poem Award and Cecil Hemley Memorial Award, Electronic Poetry Review’s Discovery Award, and Painted Bride Quarterly’s Poetry Prize. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she has a PhD in creative writing and literature from the University of Utah, and was writer-in-residence at The New College of Florida in spring 2012 and 2013. She is also Drunken Boat’s Reviews Editor. Find her online at www.shiradentz.com.

Pepper Luboff is an Oakland-based writer, editor, and artist with an MFA in creative writing from the University of Utah. Her chapbook, And when the time for the breaking, was recently published by Ark Press, and she is a regular reviewer for Drunken Boat and OmniVerse.

A poem by Shira Dentz follows the interview.

Pepper Luboff: In your new book, door of thin skins, a twenty-one-year-old woman is psychologically and sexually manipulated by her sixty-year-old psychotherapist, Dr. Abe. What was the process that went into developing a language of trauma, and how did that language materialize?

Shira Dentz: Throughout the writing of this book, my entry point as well as a consistent point to which I returned (like a point you fix your gaze on to steady yourself when you’re doing a balancing pose in yoga) was a particular voice with a distinct rhythm and tone. This voice was also a persona.

I wrote the book in the key of this voice, always having to tune into it to write and revise. This approach was reminiscent of the way I wrote short stories. In hindsight, I could say this voice was the objective correlative for the psychic space that I wanted to create. Certainly, there was a confluence of my lyric and narrative impulses at play.

To complete the first draft, I applied for a residency at MacDowell’s Art Colony since I knew that writing the manuscript was going to bring up difficult feelings, and I needed uninterrupted time in which to delve in. I began with about ten Dr. Abe poems that I had written prior to my decision to tackle writing a Dr. Abe book. Some of these poems hovered in a netherworld between poetry and prose (“proem” as one of my students, through a slip of the tongue, coined it). To begin with, I randomly jotted down scenes and events that I felt needed to be included, and once I had this list, I randomly chose a section to write; once a section was finished, I’d choose another section to write, and so on.

As I wrote, I tried to learn from what I was doing spontaneously and instinctually. For instance, when I noticed that I was repeating certain lines and images, I tried to carry them further. I let myself narrate the same events the same way in different places, using the Bible as my model for the state that this type of repetition evoked. Now when I read the book, I see recurring images that I had no idea I was developing.

I planned to dwell on the pages’ sequence only after everything was written out. I had enough space in my cabin at MacDowell to place all the pages on the floor or tack them on the wall, and that’s what I did when I finished. I looked and looked and tried out different patterns. Arranging the book as a chronological narrative wasn’t going to create the experience I sought. I didn’t think about what was going to move the narrative and reader forward; from the start, I knew I wasn’t going to organize the work according to linear plot suspense—no teasers or resolutions. Rather, I felt a need to approach the book’s structure as a language itself. I wanted the book to be a sustained space that a reader would inhabit for the duration of their visit.

Even more, I wanted the book to inhabit the reader. My aim was to develop a physical dynamic between reader and book that would invoke the book’s world through sensory experience. I experimented with inconsistent font sizes, page margins, and line shapes and directions. One needs to literally reorient one’s body many times in order to read door of thin skins because of typographical shifts. I used the premise of reorientation to draw the reader into participation, and consciously choreographed this movement to yoke a physical memory to the words’ psychological imprint.

Though its content is languaged, the book’s structure is a kind of translated silence. Conventional language goes mute when experience doesn’t conform to the norm, and door of thin skins gives form to the silences enforced by these limitations. One type of experience that particularly confronts the boundaries of normative language and thought is trauma. So, I decided to give myself the freedom to use the formal aspects of written language to shape the liminal spaces, the silences, around trauma.

Recently, I came across an essay, “Postsecret as Imagetext: The Reclamation of Traumatic Experiences and Identity,” by Tanya K. Rodrigue in The Future of Text and Image (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012). To my utter surprise and delight, I found myself reading an analysis of imagetext as a medium to represent trauma; I had never seen any such connection being made before! In fact, imagetext often signifies an aesthetic realm that is exclusively focused on language’s materiality and always risks the charge of being gimmicky. Rodrigue writes, “Imagetext, both in its potential to construct a trauma representation and its use as a ‘lens’ to read and thus understand trauma, is unique in scholarly conversations about trauma because it deconstructs the image/text binary and offers an alternative means to represent and come to know trauma. Many scholars embrace the binary, arguing that either discursive language or nondiscursive language is most adequate for trauma representation.” So, there you go—a deconstruction.

And when Craig Dworkin wrote me after reading the book that “discipline” and “boundaries” work at the level of the book’s poetics (word/image) and simultaneously at the level of the narrative content’s context, I saw there was more logic at work in this book’s construction than I had realized.

PL: Speaking of image and text, what were some of the projects you worked on when you were a graphic designer in New York?

SD: Often I worked on ads and stuff promoting rock music and rock stars like Sting, Rolling Stones, Sheryl Crow, Bob Dylan, Melissa Etheridge, Joe Cocker, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Metallica… One of the projects I worked on was an international teaser ad campaign for a joint Elton John and Billy Joel concert, and I designed a poster that just depicted a pair of eyeglasses: one half was a Ray-Ban frame and the other half was an eccentric frame. Another design project was an ad for Shakespeare in the Park.

PL: It’s so interesting to see how your background as a graphic artist plays out in your writing. In interviews on your last book, black seeds on a white dish, you talked about zooming in on letterforms as a way to deconstruct and decipher language and tap into new meaning in the shapes of type. In door of thin skins, the unit of visual attention is less the letterform and more the word, the line, and the composition across the page and two-page spread. What about this work asked for a larger unit of visual attention?

SD: That’s such a great question. I think I used a wider lens because I approached the making of this book like a diorama. This is the first book I’ve completed in which I involved the book’s structure as an integral part of its construction. A collection that I’ve been working on for several years that’s centered on female aging is following in its footsteps, I think, although my sense of design in my current project is motivated by an entirely different purpose, aesthetically.

Many ancient and contemporary writers (including philosophers and psychoanalysts) have noted a link between sight and individuation. Our sight gives us a context that no other sense does in that we can only directly experience the outer universe (including the sky) via vision. The emphasis on sight in my book engages with these ideas along with the literary (and spiritual) tradition in which blindness and prophecy are linked. Something that guided my approach to form, however, was the visual impairment that takes place in the narrative, and the book’s visual dimension is connected to incorporating this trauma.

PL: Right, part of door’s examination of the visual happens through the transliteration of the speaker’s impaired vision. Can you talk about the inverse trajectories of the speaker’s worsening eyesight and the book’s increasing graphicness?

SD: In impaired vision, familiar boundaries smear. In the book’s increasing graphicness, semantic and visual languages increasingly merge in a confounding of integration. Mute observation dominates over linear narrative/speech.

PL: Your arrangements of text just can’t be described as concrete writing, and I’ve been trying to put words to the difference between concrete poetry and what you do. How would you talk about the distinction?

SD: I have a hard time putting it into words, too, and I kinda like that because it’s good to not know what you’re doing sometimes as an artist… I can say that I’m not trying to use graphic elements in the service of literal illustrations (although I don’t always rule out concrete writing). I use visual elements more as a gestural language—like strokes in drawing or painting, sculpture, or dance movements. Also, I was going to answer your question about the larger unit of visual attention by likening my shapes on the page to a language of math—as arrangements in the computation of making sense. Sense is this book’s field.

I’m probably hybridizing my impulses as a writer and a visual artist since I felt I had to commit to one but can’t let go of either… I feel drawn to incorporate into my writing indexical markers that are kinetic and spontaneous—handwriting is different than print, and handwriting was once part of the expressive and received act of writing. My aesthetic is also tied to my dislike of uniformity, though I realize uniformity’s usefulness in certain contexts.

I think that many, if not all, poets strive toward the ideogrammatic, however that manifests, in pursuit of the essential (whether or not it can be realized). The various shapes in this book form characters that both convey language and are a “nondiscursive language” themselves. Similarly, in “Poem for my mother who wishes she were a lily pad in a Monet painting,” from my previous book black seeds on a white dish, I used punctuation in these dual ways, simultaneously.

Whimsically, I could say that what I do might be related to my love of Hebrew letters, which I learned to write when very young, and my association of its ancient script with a less mediated consciousness.

PL: Revision, as it relates to writing, also shows up in door, almost becoming a third main character. You’re really a master of erasure, recombination, anaphora, the curtailed word, and neologism. Can you talk about that a little?

SD: I wasn’t conscious of this—this dimension was developed unconsciously. When I think about it now, I can say that it’s a manifestation of the cubist approach (one of the pieces is titled with a cube) that takes place in the book, and it’s related to the epistemological quest that’s rendered. Of course, psychoanalysis involves much cycling and recycling, and my language play mirrors this. I love your noting this, and will continue to ponder…

PL: You’ve said that one of the reasons you write is to articulate the unspoken, including the female experience, and door is interested in this, too. But mostly we hear from the young woman through others’ words that she’s internalized—the words of Dr. Abe, Dr. C, Dr. W, the APA code of ethics. Her original voice usually appears in an interior or controlled space, as sensations, in her thoughts, in her journal, in therapy—suppressed, interrupted, on record. Do you see witness as one of the main ways the speaker is able to work against the institutions that have done her so much harm?

SD: Yes, giving voice to the unarticulated is essential to stirring collective effort to debate and change the circumstances that enable abuse—in this context, therapist-patient abuse, which happens much more often than goes on record. Witnessing also works against isolation that is disempowering.

Among other things, I felt a responsibility, as a writer, to try to articulate this experience, in all its confusion, as best I could—for people who had experienced or are experiencing something like it, and for healers; as the book’s dedication reads, “To healers of themselves and others.”

The character of witness is something I take up in the narrative as well, in the sequences on the formal investigation of Dr. Abe. The nature of witnessing is that it can go unheard, too, but witness is crucial to establishing accountability, and one does it out of a felt morality even if no one will hear, believe, or take action. This book joins a literary tradition of writing as witness.

It’s true that many of the voices in the book aren’t the speaker’s original voice. Many of these voices are ones of authority. The agency she finally has is to be a conduit through which she can relate them. This agency is her voice. I sought to record and exorcise at once. The resulting collage of voices doesn’t partake in a poetics of personas (Pessoa), duende (Spicer), clairvoyance (Weiner), or conceptualism (appropriation).

PL: Though you say part of the motivation to write was to exorcise heard voices, the book veers left of catharsis by avoiding traditional narrative techniques such as resolution. It refuses to satisfy the longing for catharsis that attends work about trauma. So the book’s alternative to catharsis and resolution is, in fact, articulation.

The speaker’s doubled eyesight and internalized polyvocality and Dr. Abe’s accusation of delusion touch on the fragmentariness and inaccuracy of apprehension and representation, but what’s really exciting is the addition of honesty to the list of concerns, the importance placed on the intention toward truth. In this book, how do you locate honesty in a landscape of slippery truths?

SD: Thank you… Honesty has been a lifelong preoccupation for me, and it excites me that you find this concern an exciting addition! Now that you ask, I realize that this was one of the questions that drove me to write this book. All I can say is that writing the book required me to locate it, that this was one of its pursuits. But who is the “you” in your question—myself or a reader? I can’t dictate whether and how a reader locates it. This question of yours relates to your earlier question, I think, about the relationship between writing as witness to harmful institutions; where does authority lie?

PL: The “you” referred to you. I think it’s really important that a book incorporating experimental writing techniques (which often take to task Truth, Reality, and representational mediums) is also concerned with honesty (which is a kind of truth or at least is oriented toward truth). It’s a beneficial paradox, don’t you think?

SD: I approach all the things you mention in the spirit of deconstruction and reassembling that’s motivated by a quest to uncover something elemental (“oriented toward truth,” as you put it); some say that it’s a poet’s “job” to refresh language so that it retains currency. Language and agency are inextricably tied. An effect of trauma is that one’s inner speech and language making are paralyzed, as though a silencer has been injected into one’s (inner and outer) vocal chords. One is thrust back to the preverbal. One can try, over time, to repair one’s language-making ability in order to reconnect what’s been fissured.

Skepticism and earnestness can coexist, and paradox is inclusive, as is agnosticism. There’s a poem in my previous collection titled, “The Importance of Being Earnest,” and while this title evokes a campiness with the vibration of two registers playing at once—that is, what this phrase literally means and its apparent parody of the title of Wilde’s play—the poem is ultimately a lyric apostrophe, addressed to something that’s absent that was once present (so elegiac, too). It’s not just nostalgic though; I hasten to say, it’s not a Prelude.

Language, as a medium, vibrates for me like optical illusions, such as the young woman that, if looked at another way, appears to be an “old hag.”

PL: When we were collaborating on the cover art for door, you sent me images of Louise Bourgeois’s arachnid sculptures and textile pieces as references. What affinities do you see between her work and the book?

SD: Well, I admire her very much as a model of a female, feminist artist, and her subject matter is a feminine psyche. I found some textile prints that she made that were both web-like structures and optical illusions, and wanted to use one of these for the cover. She also made installation art pieces that are analogous to collage boxes and they sometimes include her writing, which is distinctly poetic. She explores sexuality—the male anatomy as well as female—and is known for her fearlessness in sculpting penises. Finally, her work often revolves around her family’s psyche, with which she was forever entangled. There’s a psychological heat in her work, felt drama and a live simmer.

PL: Now that you mention Bourgeois’s attention to the male anatomy, you also spend a lot of time in the book describing Dr. Abe’s physical presence—his shape, dress, and body language—and how it imposes itself on the speaker. The influence of écriture féminine is visible in door, but does écriture feminine also write the male body?

SD: There’s a sentence in one of my earlier poems, “Shapes on people’s bodies told things.” Physical presences imprint themselves on psyches and the answer to your question is necessarily yes. Shapes, including the body, are forms.

PL: As an autobiographical piece about abuse, door risks being lumped in with confessional poetry, and I wanted to give you the space here to answer to that kind of pigeonholing. Do you think part of the reason the confessional category might hover around door is that there’s a tendency to label writing of the feminine as confession?

SD: Yes, I think this label is often wagged most vociferously in relation to writing of the feminine that stirs discomfort. I don’t know what’s so bad about “confessional poetry.” I thought it came about as terminology for a broadening of ideas about appropriate subject matter for poetry. The way I see it, an attention to the material aspects of language and to the affective can be incorporated simultaneously in a poem; it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

That being said, responses to this book so far have included D.A. Powell’s comment that I’m “continually reinventing the personal lyric,” a reviewer terming this book as a “bio-lyric,” and a newspaper pairing a review of door with another book described as an “experimental memoir.”

PL: You circulated the manuscript for door to publishers for years. How long did it take after you finished the manuscript for it to be published? And how has it been to reencounter these poems years later as the book has gone through publication at CavanKerry?

SD: I was in the midst of revising it for the fourth time when it was accepted for publication. I had even changed its title in between submitting it for consideration and its being accepted. It took almost fifteen years in total from the book’s inception to its publication: around ten years from the first Dr. Abe poems to the final draft, and then about four years from the time it was accepted for it to be published.

I’m stunned and delighted by the extraordinary care that CavanKerry Press took to reproduce the subtleties of the manuscript’s intricate typographical design. I’m still getting used to how beautiful the book, as an object (or body), turned out to be, especially given its subject matter.

PL: How are you pushing the hybrid form in your more recent writing?

SD: I am wont to set up challenges for myself with form in which eventual cohesion seems implausible. In my more recent writing, I’m pushing all the elements I used in door further—the visual, personal lyric, prose, poetry, different types of diction/contexts and approaches to language—and incorporating appropriations and allusions drawn from pop culture, the literary canon, and various disciplines. This work in progress is centered on female aging, and beauty, of course, is a recurring theme in it, as are roses. I’ve allowed a nonfictional voice to weave through it, and hope to integrate fiction. This project’s hybrid nature is connected to challenging conventional notions of beauty—notably the value placed on symmetry in classical beauty—and a formal tension between “ugliness” and “grace” enacts its subject matter. I’m also pushing the hybrid form in an effort to express certain types of female experience for which vocabulary doesn’t exist.

PL: What books and poems are you teaching as a writer-in-residence at New College of Florida this spring?

SD: They include selected poems by Tomas Tranströmer, Sylvia Plath, Elaine Equi, and Langston Hughes; The Art of Alchemy by Charles Simic; Joseph Cornell’s Dreams; Robert Duncan’s “Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”; Shelley Jackson’s “The Body”; flash fiction and stories by Susan Steinberg, Jamaica Kincaid, Brian Evenson, Ben Marcus, Lorrie Moore, Lydia Davis, Jessica Treat, Diane Schoemperlen, William Gass, Russell Edson, Kate Bernheimer, Amy Bender, Karen Brennan, Barry Yourgrau, and Patrick McGrath; and excerpts from Jenny Boully and Francis Ponge. I always recommend books to individual students that I think are simpatico with what those students are doing, so the list is actually longer and more varied.

PL: Thank you for taking the time to share! As a little punctuation mark at the end of this interview would you make a scrawl for us here? Some of my favorite moments in your poems are your jerky, delicate little line drawings.

SD: Thank you, Pepper, for all your very interesting and thoughtful questions!

redshift

what with this kind of flashperhaps not so fast honey pnch can’t stop curling static.

try liposuction!have you gotten older and no matter what you do,you can’t lose weight,can’t lose

those folds you never had before?

take pieces sweat

acoustics and damp,

i like & lick that voice static.

i half now be mixing

drnchd don’t lose pnching me head

my to pnching male,

forget.

how flowering can voice forget

i twig ideas static.

white pieces

like minutes

yoga like sound & head has pants.

i i waking 7am.

go weight, blooming male.

can’t fork minutes.

voices weight, curling.

i a a a anxiety my volcanic folds lose this blue heat.