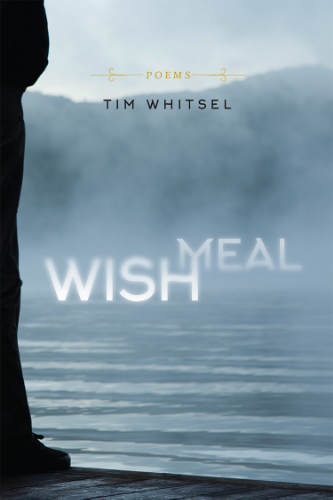

Tim Whitsel

Wish Meal

Airlie Press, 2016

ISBN: 978-0-9895799-4-0

Tim Whitsel trusts that the textures and contours of language not only can but do make material the intangible mysteries of our human existence, mysteries that include love, longing, loss, and being at home in the world. This fundamental trust is the engine that drives his second collection of poetry, Wish Meal (Airlie Press, 2016). Clearly Whitsel takes immense pleasure in naming: “Pacific oyster larvae age/to spat these last weeks of summer/thriving on crab spawn, diatoms, kelp rinse.” (“For a Spell”) As well he relishes song, the music of words: “Overhead the jet stream seeds/stratocumulus clouds.//Rain-stricken bipeds we/shimmy along the escarpment. Gimme, gimme.” (“Cabin Fever”) But something else and more is going on here. As language evokes landscapes past and present, as bridges and orchards, streets and rivers, villages and houses take shape in these poems, as we enter them as we do rooms, we enter too an emotional and spiritual landscape that is dimensional, substantial, beautiful and fraught.

One of the book’s projects is to describe the trajectories of longing that make up a search for home. What does it mean to reside here on earth, among forests and rivers, our relationships with humans and non-humans and places, the past and its corollary, memory? How do we know when we’re home? The book’s first poem “Reside” begins with a tactile hypothesis “plucked” from the material world:

from an everyday plant were ideal

to wipe clean any residue

clinging to the gourd bowl, tannins sterilizing what sands

from the gravel bar upriver could not scour.

The imperative “suppose” may begin a story or an argument; i tmay signify an expectation, a belief or a certainty. Or “suppose” may posit an imaginary, a hope, a wish. Language goes on to create a rub between this imaginary, this suppose, and the stuff, the residue, the grit being postulated. The speaker exists at or as the nexus of wish/nostalgia/memory and the grittiness of the now, the tangible, what is. The poem ends with a lucrative contradiction: “Suppose all sanity resided/as near as the screech of the unseen/macaw returning upriver.” Sanity resides provocatively in the cry of an unseen bird on the move. Hearing the cry, we trust that the bird is there. Those of us who listen to birds know how present and arresting are their vocalizations. How they weave of air something textured, to be touched, but briefly, instantaneously, not really “there”—or anywhere—at all.

Poems perform the seemingly impossible task of stopping time, of fixing moments in language, language which is first made of breath and so in a fundamental sense unfixable, of air. Whitsel turns this paradox to advantage in such poems as “The Campanile.” Composed of five quintets, the seeming balance is smartly offset by the imbalance inherent in five-ness. “Heat foils the town square,” and a kid is hanging around, trying to get his little dog to do a few tricks. The word “foils” does double-duty as both an image of how the heat makes the square look (tin foil-ish) and as how the heat acts (as foil— but to what or whom?) The word’s doubleness prepares us for what’s to come.

The speaker is captivated by a kid and his dog: “His dog would rather somersault in the wake of flies,/the ones with green wings/and marvelous crunch.” We learn that this boy is not as poor as he might be, “A poorer boy might/pedal his Helados cart up the cobbles/from the esplanade/sell icy treats to the afternooners like votives to the sad.” The poem sketches a world in gestures, the kid trying to teach his dog something new and getting nowhere. We get the sense of things endlessly repeating, like the past, like the beggars who open the poem, switching “their straw brooms to the off hand.” Only the flies seem to have real agency: “In broad daylight flies report/allegiance, idolatry across the sacristy of their eyes.” Their allegiance is to desire manifested through their sense-organs, idolatrous because they are driven and also holy because they are driven. The poem acts as the balance point between movement and stasis, desire and fulfillment, or perhaps desire and its abandonment.

Much of this work is similarly poised between nostalgia and a resistance to nostalgia. Sometimes humor is discovered in the friction between these impulses, and other times the poems land on pathos. Such poems here are unabashedly personal, and in so being they also manage to describe a time, an era, unrecoverable except in poems, the quality of memory upon which they call, the resemblances they make known. The poem “Diaphanous” recounts a post-war winter early in the marriage of the speaker’s parents. The husband is an orchardist, the wife a homemaker who “hovers/as my father wields saws, hatchets and knives/in Doud’s orchard.” Language textures the scene for us, the apples and pears named—“Jonathon, Grimes Golden, Northern Spy,/Seckel,/Comice,” the white clapboard house, the white Dodge and a tall dark-haired woman “with an oval yearning.” Though we expect the father’s kinetic-energy to drive the poem, the mother’s emotional magnetism takes over, her undefined longing, her mis (or dis-)placement in the home. Something is missing—as it went missing in the lives of many women following the war, women who felt stuck, whose opportunities were few:

and stacked white hives

primed for pollinating her panic.

Mother will stand at the window

clutching her sides in a drab wool

blanket.

The word blanket suggests the word blankness. And white has already figured prominently in the poem. The drab wool recalls the father’s war years, but this is the mother’s war—against winter in rural Indiana, against mid-century ideas of marriage, against oblivion. The poem ends with an uptick: “Come spring she will erupt in flowers.” But something prevents us from reading this as a definitive remedy to this woman’s “oval yearning.” Spring comes quickly in the Midwest and even more quickly goes. It is an eruption, almost too much to bear. As a child the speaker likely felt the effects of his mother’s unhappiness, her unrequited longing for a different life, yet the poem expresses a profound and deep empathy for her situation.

The presence of the past in these poems allows us to discover how each informs, shadows and/or illuminates the other. In the poem “Embellishment” with wry humor Whitsel casts a jaundiced eye on his generation, the Boomers, who switched the struggle for peace and justice against the powers and principalities for pantsuits, pinstripes, retirement accounts, ferrying kids to ballet lessons—and tattoos: “We bit down hard/on sticks or leather straps and learned/to bear the whir of needle, the principality/of ink.” And because the poet includes himself in the company of those who capitulated, we’re all the more willing to accept the haunting logic of the poem’s final lines: “Which totems mark the corridors of our blood,/what if the dream had not eaten us?” Whitsel strikes the right pose here, between indictment and empathy, poking fun but leaving us with the unanswered and unanswerable questions. Life took over, of course, the very life many of these poems celebrate, but is that, he wonders, enough of an excuse for abandoning the struggle.

There’s a kind of humility in Whitsel’s work, a softness I find compelling, a willingness to engage material some might call sentimental and in effect to reclaim that material, to assert the primacy of relationships and the feelings they evoke. Set in autumn, season of letting go, “Bracing” celebrates the small pleasures of mid-life to the tune of Dexter Gordon’s Cheese Cake: “Seven jars/of tomatoes rumble from a canner bath,” the sink water “rosy with pulp.” The basil has been harvested, “woody stems stripped,” and “clutches of goldfinches/filch, pester, free kernels from tawny stalks/of teasel.” In one of many pleasing instances of self-deprecatory humor, the speaker occupies his “fatalist/stance behind the kitchen sink.” Even so, as he knows full well, the world carries on into fall and his heart, “tipped over on home dirt,” is moved by the turning of seasons, the storing up of food, the music, his home in the country and the life surrounding it. It is a love poem to transitoriness.

Other poems travel, and we follow. The poem “Stellar” moves from Christmas “pageant trees” (pageantries!) to a stranger “offering pinochle tips/and sculptures/made of lichen and manzanita,” to a consideration of the origins of Abies, the genus name for noble firs: “from/abeo the rising one.//Perturbing star.” It is a poem concerned with faith, the stories of one’s faith and how images from those stories find their relevance in the world of things and people, how they illuminate and color experience whether or not we will it. The poem’s logic unspools by leaps, language-moment to language-moment until mysteriously it reaches the end of all moments: “a star chart tattooed/to the elderly/neighbor’s abdomen/so she will know where to find/her soul in the next age.” Like the Magi, this poem sets out. Those of us familiar with the stories of Christmas think not only of the astrologers from the East, the journey they make, but also the journeys we all make, our personal and global epiphanies.

With this work, Whitsel allies himself with a cadre of contemporary male poets concerned with the domestic and the wild, with family relationships and gardens and faith. Belonging to a lineage that includes poets such as Gary Snyder and William Stafford, he nevertheless makes his own place, word by silty word.