A regular feature of OmniVerse, Poets, Presses & Periodicals is a conversation with the publisher of a small press or periodical and one of our OmniVerse staff writers.

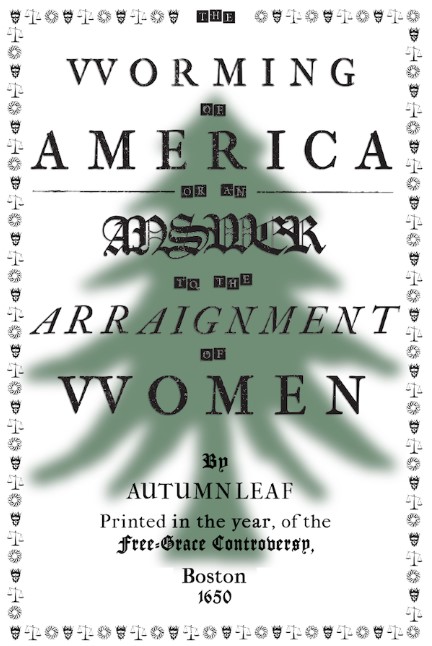

In this installment, Ariana Nevarez interviews Clifford and Jamie, the co-editors of Free-Grace Press, publisher of Worming of America, by Autumn Leaf. A short review precedes the interview.

Worming of America is available through Free-Grace Press here.

The last paragraph of the introduction to the book notes that “The Worming of America: Or An Answer to the Arraignment of Women is not just for the literate, but for the illiterate. Non-English readers are not excluded either, as all of Autumn Leaf’s original illustrations are included in this printing and they alone express and describe the novel in an universal visual language” (x). I was struck by this statement and made it a point to review and meditate on the illustrations in the book before going on to read it. These meditations revealed a story of the Haves vs. the Have-nots, of being an outsider, of power, and of fear. A story of people hanging on for dear life and being hung in theft of it. A story of monsters made up by humans and a humanity made up of monsters.

The book follows Autumn Leaf for four hours on a spring morning in Puritain Boston, 1650. As she walks to school, Autumn Leaf tells readers about the people in her community and warns against buying into any of their harmful beliefs and/or practices. Once she arrives at school, Autumn Leaf and her classmates are subject to a “theater of the absurd” in which a normal day consists of a teacher––performing a routine class inspection––calling the class to witness the behavior of a student as “post-traumatic stress disorder and/or the crippling and suicidal guilt of a murderer” (171). Autumn Leaf’s prose feels like a Shakespearean play that could be adapted for and performed in any part of American history. For example, this passage about Mary Dyer could be a scene from the Beat generation 1950’s or the hippie 1970’s:

Mary Dyer wrote that she was once again hanging with Henry Vane in Lincolnshire and also crossing through Leeds on the northern flipside, getting high on shaking and quaking with George Fox and friends… it was an enlightened hotspot in the Lake district where people went further into free-grace and their inner light… Their inner light became a guiding light, a society, a civilization –– their inner light became the Quaker religion (158-159).

A story whose setting and subject matter is far off from the minds of today’s readers, asks modern questions and carries out discussions all too relevant to today. Questions like: What does it mean to be human––“who’s in this human-race and where the beginning and/or finish line is” (6)? What happens after we die and what is the answer’s relevance to how we live? Discussions of how the child/parent relationship affects the psychology of both. Discussions of how American systems breed “self-deprecating guilt, desire, or envy for more money and power [and] is an orthodox sin that coaxes through all our American veins now” (192).

At it’s core The Worming of America is a book about feminist ideas. Feminist––as defined by Autumn Leaf––is a “polite word for an adultress and/or an anarchist in a dress. And, perchance, self-actualized, these savages in skirts will evolve into grand prophetesses or profound artists” (231). Among the many critiques detailed by Autumn Leaf is that of the madonna/whore dichotomy. Where “Mary and/or Eve are a theorem of dual vectors in which duality is a truth that works off both negative female facades, creating… extremes that play against each other… Neither abstract entity could exist without the other, proving it’s a crime, a scam, a trap –– a patriarchal control-fraud” (231). Above all else The Worming of America is a definitive and powerful answer to the arraignment of women.

Ariana Nevarez, associate editor of OmniVerse: This book sort of refuses to be one genre, permeating and pushing the barriers of multiple different genres; so, who is this book for? Who is the audience for this book/what literary community do you think it belongs to? Why do you think it’s important for this particular audience to read it?

Clifford, co-editor at Free-Grace Press: Well, thank you for that pushing barrier compliment, Free-Grace Press definitely doesn’t want to fit in. Genre wise with The Worming of America (WoA), we usually fit into one or all of: historical fiction, alternative history, women’s fiction, and/or literary fiction.

We literary published The Worming of America as a rebuttal to Joseph Swetnam’s pamphlet / novel published in 1615 titled, The Arraignment of Lewd, Idle, Forward, and Unconstant Women: or the Vanity of Them, Choose you Whether: With a Commendation of Wise, Virtuous and Honest Women: Pleasant for Married Men, Profitable for Young men, and Hurtful to None. So the book is first and foremost for Lewd women, Idle women, Forward women and Unconstant women. And more so, it is for women who don’t want to be Profitable for Young Men. Genre-wise if you liked The Scarlet Letter by Hawthorne, or The Crucible by Arthur Miller, then The Worming of America is a fresh look at that time period.

Audience and Community wise we aim to communicate with all open-minded people, but in particular the artist and writer. At Free-Grace Press our foundation and goal is the Artist’s Book championed by William Blake and his most famous book, Songs of Innocence and Experience, (1789). Since then, artists and writers have carried on the tradition of an Artist’s Book through Dadaism, Surrealism, and Conceptualism. The respect William Blake had for literary prose did not make it through to Conceptualism (1970’s). And that’s when aesthetics and philosophy dominated the Artist’s Book design so there were very few literary stories – just poetic text sometimes, and the books were mostly visual, conceptual, and/or philosophical stories. The storytelling kind of got lost.

At Free-Grace Press our goal is: publish books for our reader that are as intimate and profound as an Artist’s Book, but also tell a really good engaging story.

I think we can really do a lot with the publishing––with the industry––because it seems very stagnant in a lot of ways. If you go to your favorite book stores, all the books sort of look the same. And it’s not that we should be disappointed about that, but everyone should just be going after their own guiding light, creating their own work.

Open minded readers, artists, and writers sometimes know the history of the Pamphlet and the Artist’s Book so they may appreciate our nod to those two artistic mediums. That would be important and it’s also vital to connect the readers to an important female voice from the past and find out our struggles are identical. The female voice is in a polemic gear so there is nothing prescribed about the prose. Some readers may find that refreshing.

Ariana: Language, or the way people communicate, is an important theme in the book; what does Free-Grace Press hope to communicate to an American audience of today and what conversations does it hope to start with The Worming of America?

Clifford: I think the importance Americans would hold after reading The Worming of America (WoA) is that they didn’t and don’t understand their own history. The New England pilgrim was not just the Puritans, but the Separatists, the Quakers, the Church of England, and the Baptists (Providence, Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams who was also kicked out of Boston by the Puritans, like Anne Hutchinson). I think Americans after reading The Worming of America (WoA) would slowly realize how different America is from its original conception or birth. Life, liberty and the pursuit of spiritual happiness is just a joke now, but it was lived and died for by many early Americans. This contrast would be important to American readers because the dominant language / society now is polar opposite to this older positive spiritual language.

Jamie, co-editor at Free-Grace Press: I actually grew up on a Native American reservation and I’m part of Native American groups. What it led me to was I was able to work with a lot of different Indian Nations. And one of the things that they face, that a lot of people may not realize and other groups on the planet Earth like in Africa, are indiginous languages and tribes––which I hear is a word that’s overused in the incorrect way today. The languages from Indigenous people are threatened as we move into a digital age, because often these languages aren’t character set digitally. So, they’re fading away and people who speak Lenape for example, that language disappears. Yet with modern language––although we speak it everyday––I feel like maybe some of the conversations or the way that we use specific words, that inherent meaning is disappearing or the meaning is changing. Maybe we don’t even consider the words that we use. It’s almost like our language, besides disappearing, can become clichéd and disappear in that way. I think Autumn Leaf’s voice––which is a voice that is fresh from the past––brings up common words that we speak today, but it twists them with it’s new way of looking at things. So, like you know “parenthood” and “elders,” it just gives a different way to have insight into the same problems we all are facing long ago and today. The way we use language to communicate those ideas and the way language can either be eradicated or dissolved to cliché is a consideration.

Another point I felt was really important to explain about this book is: my entire life, when I heard about Boston and Massachusetts and that time period, it seems like the old story––the only story you hear––is the Salem witch trials. Maybe the girls were witches and maybe they weren’t witches, but it was the only story being told. So, when Autumn Leaf came to life in this book and I was able to hear her voice and understand the struggles with her mother and the struggles Mary Dyer had fighting for the concepts we believe in as Americans, like freedom and liberty you know… why wasn’t that story being told? It’s like the greatest American story to hear how these two women, Mary Dyer who actually died because of her belief and her adherence; she died for liberty and for freedom––for America. And to hear Autumn Leaf talk about that is just this fresh new belief from that period which I feel has been boxed up and suffocated with this clichéd story about the Salem witch trials.

Autumn Leaf is a real story. This eight-year old little red-headed girl watched her mother get killed––be murdered. And then Autumn Leaf was kidnapped and she literally was in the woods. She got to experience living in the woods and that type of childhood of being in the forest, experiencing nature, living––what I would describe as––a natural pattern of existence. One could say it was like an ideal Heaven. And after she was taught about free-grace from her mother, to come back to society and it was more like that patriarchal described “no this is civilization, this is better,” so she was able to experience and think about free-grace from different points of view––different cultural points of view.

Clifford: Anne Hutchinson’s father, back in what’s called the Midlands, he was arrested. He was a minister and he was put under house arrest during the English Civil War, because they were Separatists. The Separatists in the English Civil War turned into Quakers after they lost; they didn’t know what to do. So, they muffled the violence with Quakerism, but then the second generation of Quakers got very violent and started the American Revolution. Thoreau, you know his Walden (1854), he’s always given the credit for Civil Disobedience. We were trying to steal it from him and give credit more to Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson, because they were the first

people that peacefully broke the law and fought “The Man” or the “Elders” or what have you and he made it much more popular in Walden. He just barely mentions he was arrested during the experiment in that book, but he’s always given credit with Civil Disobedience which was the seed for Gandhi in India and Martin Luther King Jr. in the south.

Ariana: The Worming of America discusses a lot of different dichotomies and dualities––Child/Parent; Lightness/Darkness; Insiders/Outsiders; Men/Women; and The Natural/The Man-made to name a few––when are dichotomies and dualities helpful and when are they harmful to people? Why does the book include so many as themes?

Clifford: Well the complicated themes require critical thinking and compared to the mass media––which makes everything into an easy multiple choice––the duality debates can be confusing to some, but a fun puzzle for others. This philosophical prose is thick and leaves readers alone with a lot of questions and no directions to escape. These duality debates or binary relationships are a large part of mathematics and physics. So when Autumn Leaf debates or deconstructs a theme, I suppose these binary relationships are an easy way to compare and contrast––side by side––literally.

These dual relationship formulas can be harmful like all formulas because they don’t take into account outliers, odd balls, and things that don’t want to fit in.

Jamie: The reason they were suppressing Anne Hutchinson is what comes out in Autumn Leaf: the concept of free-grace. That is maybe another binary if you look at mainstream religions today and at the dichotomy of good and evil. In Anne Hutchinson’s case, she was really advocating for free-grace, meaning you’re saved not by your work, but by this other spirit. I think if you really get into American history and look at some of how it was actually formed, there is this sort of burden or emphasis placed on good work. And then when you hear about how Harvard reacted so strongly to this woman who was advocating for free-grace, it’s another layer of religious oppression where people can’t just be enough based on who they are––their spirit––they have to adhere to what the patriarchy, or the elders, or the hierarchy says is good work. You have to subscribe and conform and meet those binaries and check the right box. It seems like you’re always talking in binaries about this or that and even the media narrative today––it’s like you either believe this or you believe that, but there’s not a lot of mainstream media addressing the points of the outliers, or people who don’t fit into those boxes, or the one-off cases which are usually more interesting, more artistic, more nuanced, and ultimately add to a richer dialogue.

Ariana: It looks like there was a lot of thought and work put into the campaign for this book. There are T-Shirts available on the press’s website, photos of women draped in fabric printed with illustrations from the book on the book’s own website, multimedia outlet advertising, and the book itself feels very high quality––complete with an attached ribbon bookmark. Can you speak a bit about the book and campaign design? Why was this so important for this book?

Clifford: Speaking to the book, it’s design and the PR around the content we have to state clearly that Free-Grace Press is not publishing because we want to make money––we’re publishing because this is our art and we want our work to be high quality. Therefore, we are thinking everything through not as publishers, but as artists creating an Artist’s Book. This could throw some readers or those in the literature world, but we hope those with an open mind will appreciate our publishing work and be engaged and entertained.

Free-Grace Press also published two Worming of America audiobooks. One was read by a female actress and another read by a male actor. This was a great experience in artistic collaboration for publishers because we had to coach and direct the actor’s intonation, rhythm, speed, pronunciation, accent, etc. The male Boston Edition was recorded by Keith O’Brien in New York and the female London Edition was recorded by Katherine Roden in London. This was a lot of work to say the least, because we also recorded musical interludes, sound effects, and songs, along with the text. Regardless, we’re really proud of our creations and look forward to producing more audiobooks.

The audiobooks and all of our public relations work feels like the preparation for a theater production or movie––maybe someday!!!

Ariana: That’s very interesting; what was the difference in direction for the two readers?

Jamie: The two audiobooks came about because Clifford and I couldn’t really decide what was the best voice for this book initially. We got stuck in kind of the binary argument, if you will: Would the audience prefer a man or a woman? And what it led to is what we both consider to be two pretty amazing people. The ,if you will, male version––Boston version––was done by Keith O’Brien. He’s done other audiobooks and he’s actually a jockey and I consider the work that he did on the Boston version of WoA to be one of the best audiobooks I’ve ever heard. He becomes the characters. At some points, you know, hearing him in the last chapter when Mary Dyer was being hung, I was so struck in silence; I was so moved emotionally almost like I re-heard the book again for the first time and it just took me through all these emotions. It was like poetry hearing him speak, but then almost a completely different take on the book was when Katherine Roden did her version. She’s an actress trained at Oxford and she’s… you know, her voice, to me, compared to Keith O’Brien who became a storyteller––he almost transformed into fifteen different people––with Katherine Roden I really distinctly heard Autumn Leaf as a young woman. Kind of with the fragility, and the anxiety, and just the suffering she was going through––I could definitely connect with the book on a more intimate, personal level when

hearing her speak. So, the UK version is very distinct and unique from the Boston version. I felt with this book bringing Autumn Leaf’s voice to light in today’s world, it’s almost like it’s so fecund that it just spills over like a fountain into all these new endeavors of art––it’s just like a flowing river of creativity.

Clifford: From my point of view, it was more that I always imagined an English woman or a UK accent reading it. We were auditioning women from Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, much less just all over the UK and Scotland and Ireland and also America obviously, but it was great to work with the women who were reading and even we opened it up to men and Keith was so good we had to hire him.

Jamie: We absolutely had to have him.

Clifford: We had to and it’s a lot to read, it’s a lot of characters and he needed no direction. Katherine needed a little bit more direction and a little more coaching because she didn’t know how to say Pequot or Lenape, because you know, she wasn’t familiar with the pronunciation, but it was a great experience to coach and to work and to listen to it.

Ariana: The spine of The Worming of America declares this to be “I of V” books for Free-Grace Press. The titles of the next four books to be published by Free-Grace Press are listed on the press’s website. The next book to be published in 2021 shares a subtitle with The Worming of America, and the title of the trilogy that will follow mentions “Free-Grace,” a central theme in The Worming of America. In what ways will all these books be in conversation with one another?

Clifford: Thanks, that’s a great question. All five books will investigate the Free-Grace Controversy (does one live for spiritual good or a material good?). Worming of America converses about how early Americans largely chose to live for a spiritual good and I think the American mantra––of living for Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness––is an evolution of free-grace thought and living for a spiritual good.

Our second publication in 2021 is Mother’s Day in the Empire State, Or, An Answer to the Arraignment of Women (MDES). And like WoA, it is also narrated by the daughter of a famous heroine. With MDES the spirit of femininity is again critiqued, but this time it dials down on

how money affects motherhood. This book describes and debates how motherhood within poverty is different from motherhood within luxury, and most important––how does this economic difference affect the children emotionally, financially, and physically.

The next three books, Sagg, Or, Life in Free-Grace will be a trilogy and will examine how unknowingly, a contemporary American male (divorced father of two children) deals with the many questions Henry Thoreau brought up in his book Walden; Or, Life in the Woods. Thoreau’s experiment in the woods, we believe, was an evolution of the Free-Grace Controversy––living for a spiritual good, in harmony with nature. So in Sagg a divorced father of two in America discusses / debates how he can keep a relationship going with his children and at the same time evolve spiritually. With the Sagg trilogy, we’re connected and we’ll come full circle back to Autumn Leaf / WoA and the discussion / debate still being about whether you live for a material good or a spiritual good––one in 1650, another in 2022.

Ariana: How did these five books come to you? Do you plan on publishing more, or are these five going to be the focus of Free-Grace Press?

Clifford: I think right now we’ve shot it through to 2024 and this isn’t our day job––this is our art. So, we have to take our time with it. All the publications are going to be in the same vein of 30 illustrations and the similar themes, but I’m open to meeting other authors and working with and publishing them.

Jamie: The focus too is as we finished the last one and doing all we could to promote it… it was definitely a lot of work. It’s not like we’re making movies where we see a great return on investment. So, identifying the right kinds of authors that won’t make us go bankrupt, but that we believe in and support the whole concept of challenging the language, look to promote the individual spirit, and challenge the clichéd common narrative is I think something we’re both passionate about. And that sort of came into some of the collection. The books are rather challenging, so that’s something we’re thinking about and also how to find other artists to work with. There’s a lot of people who have books written, but maybe they’re not sure about how to

publish. So, we’re definitely looking for new artists to work with who are sharing the same vein of thought.

If you know any artists who are looking for a publisher, let ‘em know about us!

Ariana Nevarez is from Berkeley, California. She graduated from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo with a B.A. in English. She is a part of Omnidawn’s social media team and is now a contributor to OmniVerse. She lives in Boulder Creek, California, happily surrounded by redwood trees.