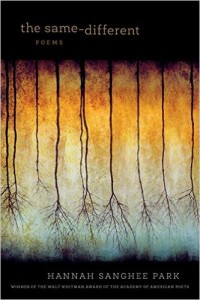

Hannah Sanghee Park

The Same-Different

Louisiana State University Press, April 2015

ISBN: 9780807160091

In her debut collection The Same-Different, Hananah Sanghee Park inspects likenesses— a word that, in her hands, suggests similarity, attraction, deception and artistry. Her exploration is lexical, imagistic, and theatrical; Park puns, riddles, and shape-shifts her way through meditations on self-recognition, persuasion, and loss. Addressing an elusive lover, Park’s speaker quickly shifts her attention towards the nature of her speech itself. Overbrimming with intelligence and music, Park’s dense lines owe as much to Gerard Manley Hopkins as to Liz Waldner. Her language becomes a place of likeness and also rupture, inviting entanglement and also evading it.

“Things fit together,” writes Jack Spicer. “We knew that— it is the principle of magic. Two inconsequential things can combine together to become a consequence.” For me, this maxim captures the magic of Park’s lexical play. But instead of creating new combinations, Park’s poems take things apart, revealing the morphemic alchemy that is already present in the words that describe our world. “Just what they said about the river: / rift and ever,” The Same-Different begins, suggesting both the loss inherent in this fragmentation and its expansive possibility. In the opening poem, “Bang,” words are made, dismantled, and rebuilt in couplets:

as scribes capture

meaning all that was there and only

(one and lonely)

is all that is left, and wholly

whose folly.

The sky bleached to cleanly

clear, evenly

to have left the world

to what is left of it…

This poem buzzes with the generative power of combination. Under the speaker’s searching gaze, a river, horizon and sky are destroyed and rebuilt. Words fragment and bind themselves into new words. This merging and separating is also a mimesis of seduction, and the poem concludes with an invitation: “Could you have anything left to covet? / Covertly met: coverlet. Clover, bet. Come over et— ” The title “Bang” could be referencing the world’s creation—or perhaps sex, an accident, shock, or spectacle. In all these possibilities, “Bang” uses language play to call us back to our own embodiment. As this poem unpicks language, it changes the spatial and temporal nature of our reading experience; we look backwards to split a word apart, and look ahead to reconstitute it in the next line.

Alongside the linguistic metamorphoses of her poems, Park executes dazzling imagistic transformations. In her landscape “the logs wear temporary casts of frost,” and the sky is “the color of being photocopied too many times.” Vivid glimpses surface and then shape-shift into each other, as in this poem, “Strip”:

carried a carcass, a carapace,

and its own casket in another casket,

its own natural sarcophagus.

I never told anyone this story:

In a summer like this I ate a nectarine

until its rough corduroy pit, continued

rolling and chewing it until it hinged

open, and an inert spider, sitting

in white wisp, was inside like a small jewel.

Leapfrogging from object to object, “Strip” builds a chain of visual likenesses. With its delightful attention to sound, shape, and the minutia of the natural world, this poem seems like a descendant of May Swenson’s. But in its final lines, the poem pulls back, breaking into a new, meditative voice:

comprising me are, reductively, soft

hard, soft, an easy sift to the truth

but the hard sell and swallow done anyway.

These couplets act “reductively” to “strip” the poem down to its simplest imagistic pattern: “soft, hard, soft.” In a parallel shift, the speaker’s voice is tonally stripped; it grows plainspoken, direct. As The Same-Different unfolds, this pattern of observing and then disrupting formal patterns becomes the collection’s signature. Tightly controlled poems open outwards into expansive last lines or disarming plain speech. Sameness and difference manifest through formal experiment, as Park subtly shifts her terms and revises her own procedures.

The book’s central poetic cycle, “Mutation, ” takes up transformation as both subject matter and formal engine. This section considers twelve myths of “chimeras, hybrids, or shapeshifters”: Baba Yaga, Ammit, the Jackalope, and the Deer Woman, to name just a few. These poems unfurl across a calendar year, with each month offering new potential for metamorphosis. The opening poem in this sequence, “Narcissus in January,” explores the ways self, lover, and landscape blur:

and weigh the sum of stem and blossom, plus

or minus my reflection’s heft—it was

the undoing, it was all I had else the man,

and the water’s surface where we end, ends me.

In these lines, identities multiply and split apart. Exactly how much can this “I” encompass? Is Narcissus made up of “blossom” and “stem,” or is the speaker more than the “sum” of his embodiments? Does “the man” refer to Narcissus’s human form, or does the poem reach outwards towards a separate beloved? These fragments of selfhood coalesce into a “we” that shimmers on the water’s surface, threatening to eclipse an illusively singular “me.” An emblem of sameness and difference, the myth of Narcissus haunts this collection. Narcissus exists on the troubling boundary between self and other, unable to either split away from or merge with himself. Proceeding from this opening poem, the “Mutation” cycle explores alternatives to Narcissus’s impossible stasis, invoking figures who find generative, tragic, hilarious, and regal possibilities in their own transformation.

The final section of The Same-Different, “Fear,” is an expansive serial poem that unhooks itself from the book’s organizing conceits. We’ve followed quick-witted investigations into word, image, and dramatic personae. Now Park seeks out other forms, pushing beyond the individual unit of the poem into an extended meditation, stretching out across white space, delving in and out of voices. Modulating between image and address, “Fear” intersperses wrought language with transcriptions of intimate conversation:

Again you: why? and how? and what company am I

keeping?

Only that of someone whose liver is

a lily, whose lover was a likeness

in this light— come here, I’ll show you—

everyone has a likeness,

not so much a light.

Flickering between human and flower, self and other, body and voice, the couple in this poem construct a closed circuit of identities. To answer her lover’s question, “what company am I keeping?” the speaker describes herself in terms of the person she’s talking to. She is “someone… whose lover was a likeness…” Is she also describing her lover in terms of herself? The word “likeness” has been richly faceted in this collection to suggest mirrors, twins, portraits, counterfeits, and just plain “liking.” The speaker invites us to “come here” and peer with her into the many possibilities of this word—which are, at this point, also her relationship’s possibilities. If “everyone has a likeness, / not so much a light,” we are lucky to have Park’s bright attention guiding us through these poems, illuminating shifting identities, intimacies, and the words we use to describe them.

Liza Flum is a lecturer at Cornell University, where she recently received an MFA in poetry. She is also a poetry editor for Omnidawn.