Review by Lina ramona Vitkauskas, Chicago Correspondent

What’s The Matter Here?

Why are you here tonight?

Are you hoping poetry will save you from the self-help gurus?

Are you eyeballing the exits?

Are you lost?

Are you looking for the restroom?

Are you searching for a distraction from the “you” that “you’ve” become?

Are you entertained by language?

Are you going to hell in a Harley-Davidson basket of derivatives?

Are you bored with being boring?

Are you in over your genitals?

Are you looking for a community of likeminded individuals for when the apocalypse finally comes?

Are you insured against major life-changing poetry events?

What’s the point of witnessing the poet’s biography during a reading?

Do your ears ring with unsaid character development?

Do your eyes water with ineffable images?

Do your nostrils flex with the strong silence type?

Do your fat palms sweat touching implicit hips?

Does your mouth water on the cutting edge of applause?

— Gene Tanta, “Why Do You Come to Poetry Readings”

On an unusually warm spring evening for Chicago (April 12, 2014), poets attempted to answer the above questions—if not literally, then conceptually—with more poems of their own. Local poets gathered at MATILDA/Baby Atlas in the Lakeview neighborhood for the First Anniversary Reading of the online journal, Matter.

On an unusually warm spring evening for Chicago (April 12, 2014), poets attempted to answer the above questions—if not literally, then conceptually—with more poems of their own. Local poets gathered at MATILDA/Baby Atlas in the Lakeview neighborhood for the First Anniversary Reading of the online journal, Matter.

Matter: A Journal of Political Poetry and Commentary is edited by Virginia Konchan, Glenn Shaheen and Michelle Sinsky. Konchan and Shaheen hosted the event, and readers included local Matter contributors: Holly Amos, Heather V. Cramond, Laura Goldstein, Carrie Olivia Adams, Virginia Konchan, Jennifer Karmin, Gene Tanta, and Lina ramona Vitkauskas.

Shaheen opened the event with a wholehearted thanks to all who have helped make Matter a significant journal in its first year, and the readings that followed brought forth themes of class war (pay inequality, corporate welfare); pre-emptive (unfounded) military occupation in Iraq; violence portrayed in the media; and more.

Readers Jen Karmin and Laura Goldstein—co-curators of the collaborative, ten-year-running Red Rover Reading Series (readings that play with reading)—undertook the topic of violence in two distinct ways: Karmin in direct context (war); and Goldstein in a more impervious way, shedding light on the media’s role in perpetuating violence by how it is portrayed.

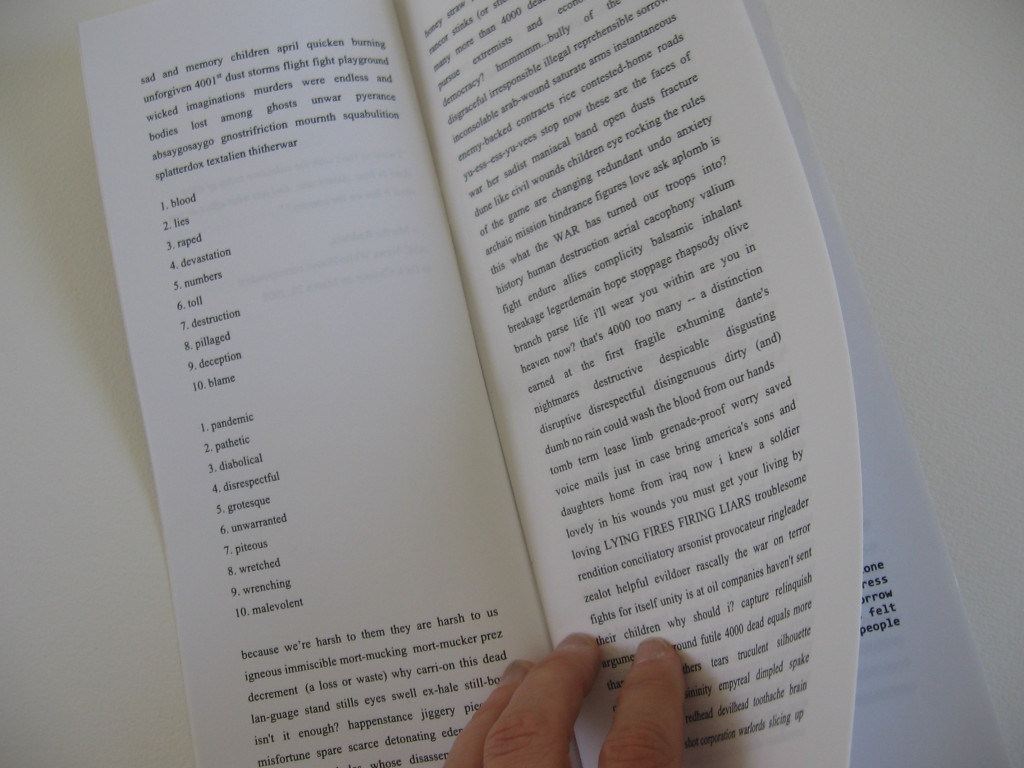

Karmin read a compelling excerpt from her Iraq War litany 4,000 Words 4,000 Dead & Revolutionary Optimism/An American Elegy (Sona Books, released for Veterans Day 2012 and then online for Memorial Day 2013).

“In April 2008, I began collecting 4,000 words as a memorial to the 4,000 dead American soldiers who had been killed in Iraq,” mentioned Karmin. “Submissions came from friends, students, writers, activists, soldiers, and those who read about the project online. I asked each person to send me one to ten words, gave parts of the poem away to pedestrians during public performances across the country, and painted the words using the American flag as a writing utensil in two installations.”

(from the chapbook, printed and handmade by fellow poet, Jill Magi).

Goldstein read from her chapbook titled awesome camera (Make Now Press). awesome camera “is cored around the question of how ‘the media’ mediates our witnessing of the suffering of strangers,” writes poet Divya Victor. “The camera, like a tiny high-tech coffin, seems to trap both the corpse and the viewer into an uncomfortable intimacy that only one can survive.” Pieces of Goldstein’s awesome camera appeared in Matter’s first issue.

(An excerpt of the chapbook on Matter.)

Lina ramona Vitkauskas read from a 2013 poetry collection, Professional Poetry (White Hole Press), which was created twofold as, 1) a response to the most recent, blatant rise of “careerism” within the “poetry world”; and, most importantly, 2) a dedication to all of the struggling adjuncts within the university system (due to the grossly unfair discrepancy between administrators’/ tenured staff pay and benefits, and the instructors’/adjuncts’). The collection uses various professions thematically to generally comment on the US jobs market/economy (Vitkauskas herself a current low-wage earner from a blue-collar family of Lithuanian immigrants).

Finally, perhaps in the spirit of what lately seems to be eroding love between our brothers and sisters (all over this land), Holly Amos read her poem, “If my mouth weren’t so full of hammers”:

I’d be a better bride to this world. I don’t mean to be so female. Lately my hair isn’t even clean. There was a time I could stand outside & feel the wind making use of me. My mother built a pond I no longer swim in. Someone will inherit those rocks & the labels I gave them: Midwest queen, secret-keeper, kin to knees. All the good jokes about time are taken; instead I hold its face in both hands & refuse to move away.

Overall, the evening offered up stimulating poetry by all and insightful conversations post-event. This OmniVerse correspondent had an opportunity to engage editor Virginia Konchan to ask a few questions about Matter, the state of the world today and how poetry responds to it, and what is “political” in this “post-everything” era:

LrV: What inspired you to start Matter?

VK: Glenn and I read together in 2013 at a “Monsters of Poetry” reading in Madison, WI. We conversed afterward and recognized many shared sympathies (prevailing trends in contemporary verse and directions we hoped to move in, collectively and in our own work), we began discussing how to write without self-censorship while within the auspices of academe (we’re both PhD students in Creative Writing – poetry). Within a few weeks, we’d crafted a mission statement, invited Chicago poet and translator Michelle Sinsky to join us, and Issue One, in May 2013, was launched!

LrV: What are three major foci of the journal?

VK: Achieving gender parity by actively soliciting the work of women, minorities, and, increasingly, from the international community; risking deploying the word “political” in our journal name (an empty signifier long since dissociated with aesthetics, in theory and practice) while not feeling pressured to define that word; and to establish a lasting presence in the virtual age as an online journal with no carbon footprint.

Our minimalist site and quiet web presence (Twitter, FB, and Duotrope) allows the excellent poems we are privileged to publish to attract a developing readership organically, without direct solicitations, ad banners and campaigns, creating a non-bipartisan public space for a dialogue of literature and politics (along with the buried affects, amid the glibness of pop culture, and repressive state and market apparatuses, of grief and rage).

LrV: What do you hope to achieve (on a broader scale, for non-writers) by doing Matter?

VK: If language, as Emerson said, is fossil poetry, resurrecting a “market value” to literature beyond price is as political an act as I can imagine, for the continuance not only of subjectivity, but the work of valuation, care, and recovery from personal and historical trauma. The Catch-22 of any gift economy is, of course, economic survival of its subjects, yet Matter and other journals with a strong online presence, capacious aesthetic, and fiercely good writing (Memorius, Sixth Finch, Vinyl, Jubliat) are sustained volitionally, as is any non-transactional relationship: the fruits of this volunteer labor is the shared currency or surplus value of mutual respect and community. A revolution in language and of language, wherein we are all either liberated (as conscious rhetors and writers) or (through complicity with media-speak, propaganda and advertising) enslaved, is at hand. Demotic speech, delight in language-as-ornamentation, erasure and documentary poetry, and poetries re-appropriating government and public documents all help undermine the institutionalization and sterilization of language. We hope to foster these fluid contingencies for years to come.

LrV: Why do you feel it (Matter) most relevant at this point in time?

VK: Anesthetizing ourselves on lies and hollow forms leads to two equally disastrous ends: death, or the illusion of life, while dead (aesthetic or virtual necromancy). That’s where we’re at. Alternatives have to be forged, and venues for dialogue created, despite resistance: when dictatorship is a fact, revolution becomes not just a right, as Victor Hugo puts it, but a necessity for survival, of the environment and human life.

LrV: Class warfare abounds in the US. Wages paid for many service jobs are not commensurate with skyrocketing cost of living. Talk a bit about how this widespread problem has also affected what’s happening to adjuncts teaching creative writing in this country (highly publicized by mainstream media and credible sources: NYT, Salon, Chronicle of Higher Ed, HuffPo) and why it’s important. How does it relate to the mission/goals of Matter?

VK: Fundamentally so. My conversations with Glenn about writing within the academy are what prompted the creation of Matter, and while I can’t speak for Glenn and Michelle, nor our contributors, I believe we, as an independently funded journal (not receiving state, or academic, support, nor reliant on reading or contest fees) are alive to the question of unpaid and underpaid labor (including that of free intern labor – a compulsory stage for many college grads today, already burdened with debt, yet desperate to believe the cant that a remunerative job results from “paying one’s dues”).

All money may be “dirty” in the sense that interests are self-fueled (a metaphor for privatization, of education and natural resources), but the system of post-empire disaster capitalism, of which higher ed is a blistering symptom ($1 trillion in national student loan debt now toppling national credit card debt), is a virulent disease indeed. As educators, we join, however helplessly, in the trumpeting of the liberal arts over practical job skills, vestiges of a Cold War rhetoric prioritizing aesthetic achievement whose players (adjuncts, lecturers, visiting, or non-tenure track professors with teeming job responsibilities, little job security, and no seeming alternative other than bartending) are increasingly unable to feed, clothe, or house themselves.

This quagmire reflects the structural inequity and power asymmetries at the heart of capitalism: supply (e.g. specialized craftspeople in the literary arts) has outstripped demand, a crisis not just for the creative class but the US economy, as fewer market subjects have purchasing power. Corporatized higher education, buoyed by standardization in the public schools, creating a new generation of debt slaves, is highly ironic impasse to progressive growth and quality of life in a country founded on an imperialist silencing of the “other” (genocide of the Native Americans; a slave economy), rendered dangerous unless chained to factories wherein the laborer cannot get into the “black” (also of signification), making minimum wage while paying off exorbitant debts. The facts are ubiquitous: Sallie Mae, a company originally created by the government but now fully privatized, epitomizes the danger of depending on the “free” market to provide a public good: as it approached full privatization, Sallie Mae had a total portfolio of student debt near $100 billion while, from 1999 to 2004, Sallie Mae’s top two executives, Al Lord and Tom Fitzpatrick, received compensation worth $225 million and $245 million, respectively. After buying up competitors, expanding into the loan servicing, loan guaranteeing and debt collection business, Sallie Mae cut deals with for-profit colleges giving Sallie Mae access to its students and boosting its portfolio of subprime loans from $7 billion to $15.8 billion, while lobbying to make student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy as part of the overhaul of bankruptcy laws in 2005. After the housing bust, according to the 2012 class action suit, Sallie Mae aggressively pushed students at high risk of default into forbearance — a stopgap measure pushing technical default into the future, and off Sallie Mae’s books.

So, is education an absolute good, especially advanced degrees in the fine arts? Questionable, given these funding and labor structures, to say nothing of the history of unionization denied to faculty on the claim that professors belong to the managerial class. The 1968 revolution in Paris, uniting workers with students, could provide a model: the intelligentsia and disappearing middle class, are both in dire straits, yet can solidarity be achieved within academia, or solely outside, through microcommunities of Anne Waldman called “magpie scholars,” and independent publishing circles? Classism and the rule of the 1% may well dissolve were we to find a way to fight for collective and not individual interests, especially in unionized workplaces: faculty and a janitorial staff protesting inflated administrative salaries and low-wage exploitation together, without fear of reprisal were a tenured faculty member to support oppressed faculty, staff, or students nerve-wracked about their debt or career path, dramatized in several scenes in exposes of academic usury, At Berkeley, and Ivory Tower, without fear of job loss.

LrV: What is “political” to you?

VK: Risking sensitization, and awareness of the other, and our shared responsibility to the call of the other (or tortured cry): the ethics of rapprochement with the human face that, according to Emmanuel Lévinas, orders and ordains us, interpolating the subject into an dialogic, I/Thou relation.

How we treat ourselves and each other is related to how we use the finite resource of language (speech, writing, gestural and non-logocentric forms of symbolization), as well as our ecological orientation. Like revolutions in language, revolutions in ecology stem from concerted efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, phase out nuclear energy in favor of renewable energy, create “green jobs,” refuse to buy products or patronize stores reliant on exploited labor (however imbricated a web), support fair and direct trade businesses, green housing, sustainable agriculture and a moratorium on the use of GMO crops.

We can’t actively choose co-existence over mutually assured destruction, or fight against sexism, racism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination if the very earth we inhabit is perishing from the toll of indifference, toxic lifestyles, and corporate greed. The endgame to eco-devastation is, I fear, a rationalization of our fetishization of violence, inanity, consumerism, and a society of the spectacle. Somewhere beneath the rubble are human bodies, human voices, and idealisms waylaid by post-ironic kvetching. Matter is a place for unearthing these subjects, validating our constitutional rights for speech, press, and organized assembly, and finding humor (especially of the parodic vein) in restoring a more balanced “humanity” (provisional scare quotes, as with “political”), along with machines and animals—anthropological biodiversity—to the scene.